On a rainy day in June 2020, Georgy Froté got up and went for a walk at the Balgrist University Hospital on the shores of Lake Zurich. Taking one step after another, he succeeded in walking 17 meters entirely on his own. “Nobody thought this was possible!” he says, wishing he’d gone farther. Froté, who is from the Jura region, lost the use of both of his legs after a serious motorcycle accident in 2010. However, thanks to a new device developed by Grégoire Courtine, a professor at EPFL, and Jocelyne Bloch, a neurosurgeon at the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) – along with years of intensive training – Froté was able to regain some of his motor function. The device includes electrodes that were implanted just below the damaged area in his spinal cord in 2018. These electrodes are connected to a neurostimulator that generates electrical impulses similar to those naturally emitted by neurons, causing the legs to move.

Froté’s road to recovery is long and hard, but he has now “taken the first step.” And this achievement wouldn’t have been possible without Courtine and Bloch’s device – the result of a decade of research on animals. The research team initially tried out their device on paraplegic rats that were implanted with the electrodes. The next step involved running computer simulations to see which neural connections could be stimulated by the electrodes. With that data, they further tested their hypotheses on genetically modified mice, other rats, and finally macaques before conducting clinical trials on humans. “All these different steps in understanding the mechanisms involved were essential for our human trials to work right from the start,” says Quentin Barraud, deputy of prof. Courtine at EPFL. “Today our device has been implanted in nine patients with either full or partial spinal-cord injuries. And every single one of those patients has regained some motor function.”

Modeling scientists’ hypotheses

To support the development of new treatments and therapies that can help people like Froté, EPFL set up several animal facilities in 2009 which today house nearly 20,000 mice, 660 rats and 18,000 zebrafish. Switzerland requires that all research projects that will involve animal testing obtain approval from the cantonal veterinary authorities, who work in conjunction with a cantonal commission for animal experimentation, composed of both specialists and animal protection representatives. Scientists must specify in their application forms what information they hope to obtain from their experiments on animals, which experimental procedures will be performed, why those experiments are absolutely necessary and the maximum number of animals that will be used. Scientists must therefore demonstrate that animal testing is necessary and will be carried out appropriately. Otherwise, the office could impose conditions before approving the request, or, more rarely, refuse it.

It helps mice get used to the presence of humans”

Going inside one of EPFL’s mouse housing and testing facilities entails going through a strict protocol of donning a lab coat, bouffant cap, gloves, disinfected clogs and surgical masks. The cages are arranged in racks and each cage is equipped with its own ventilation system, such that the entire structure looks like a multistory apartment building. Each cage is lined in sawdust and equipped with various objects such as a red plastic dome and a cardboard tube where the mice can build nests, play, group together and sleep. No more than five mice are housed in a given cage. A radio is left on all day long in order to provide background noise. “It helps mice get used to the presence of humans,” says one of the animal caretakers at EPFL’s Center of PhenoGenomics (CPG), the unit that manages the animal facilities.

The testing area in this facility contains several rooms, each for a different type of experiment: ultrasound scans, mazes, endurance tests and so on. The animals are bred specifically for research purposes, meaning they will be used to study a specific disease – cancer, a neurodegenerative disorder, obesity or COVID-19, for instance. Verifying scientists’ hypotheses generally requires a substantial number of animals.

“Scientists can’t just do whatever they want”

Some 50 research groups at EPFL need mice, rats and zebrafish, and a total of around 65 people care for EPFL’s animals, making sure the right procedures are followed and the animals are treated properly. If the rodents fall ill or are injured, the CPG veterinarian steps in to treat them. The CPG’s animal caretakers spend most of their time with the mice and often become attached to them. “A bond is definitely formed. Even if all the mice look the same, you never get used to knowing that at some point they won’t came back from an experiment,” says an animal caretaker. A PhD student who is performing a scan on a sleeping mouse agrees. “I’ve become accustomed to working with the mice, but it’s not something I want to do after I graduate,” she says. “Animal suffering is difficult for me to watch, even though I’m able to be objective about it.”

At EPFL, 93% of animal testing procedures range from sub-threshold to moderate in terms of severity, and most of the testing is non-invasive. But the suffering caused to the animals, as well as the euthanasia that’s almost always performed in order to conduct post-mortem analyses of the animals’ tissue and organs, are sensitive topics. Xavier Warot, head of the CPG, explains: “Scientists can’t just do what they want. They have to weigh the constraint caused by interventions or measures carried out in an experiment against the benefits that the research will provide to society and scientific research,” he says. What’s more, the results of research done with animal testing are reliable only insofar as the experimental data themselves are reliable. That means the animals cannot be placed under stress or treated poorly, otherwise the results will be biased. “If the animals are unhappy or stressed, the data from our experiments won’t be valid and all our research findings will be compromised,” says Quentin Barraud. “Taking proper care of the animals is part of a professional approach that adheres to the highest research standards.”

If the animals are unhappy or stressed, the data from our experiments won’t be valid”

Keeping the number of animals to a minimum

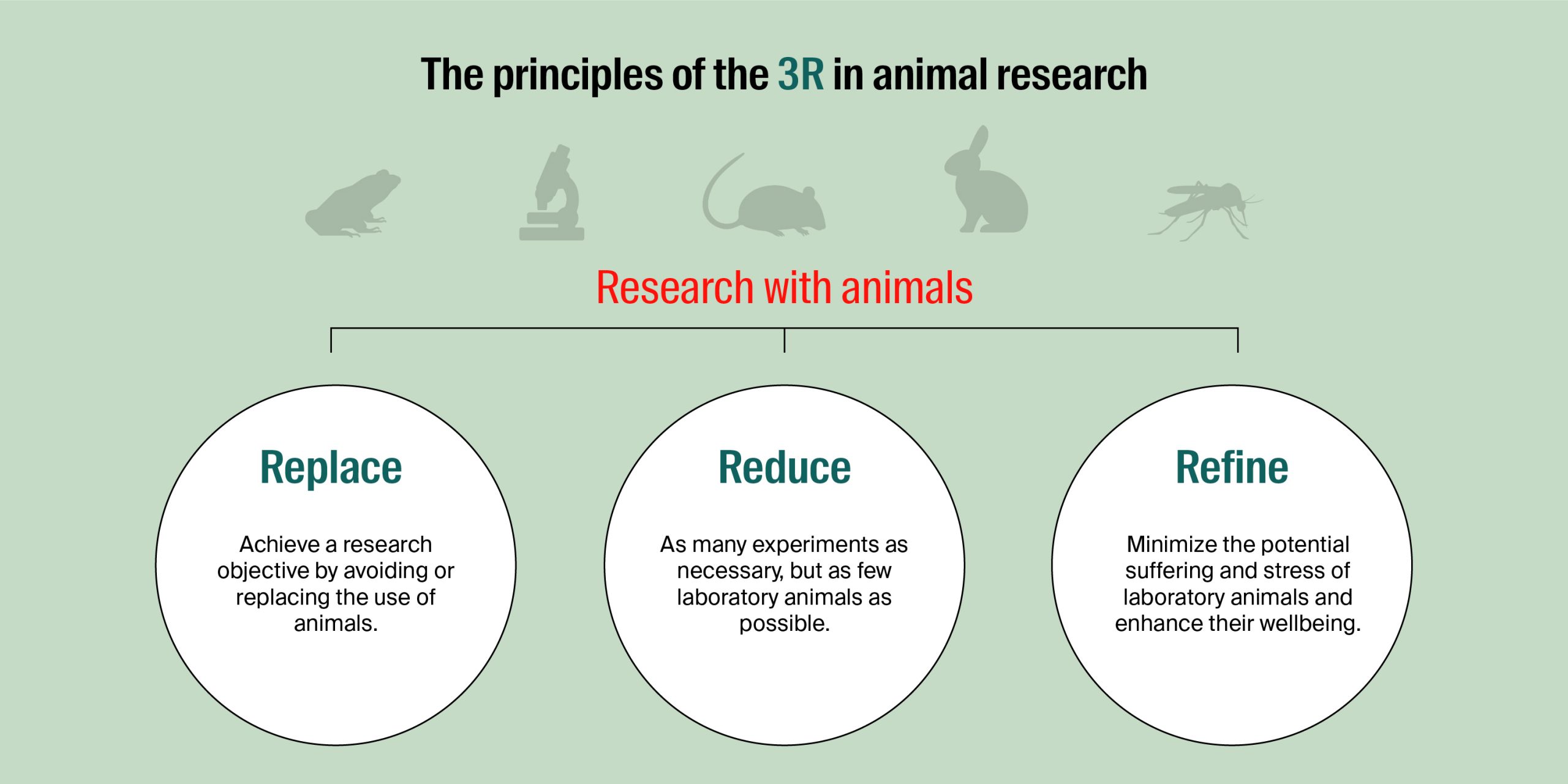

Animal testing is permitted in Switzerland only if no other form of testing would be feasible. At EPFL, scientists follow the 3R principle: Replacement, Reduction and Refinement. This principle is promoted in Switzerland through the Swiss 3R Competence Centre, established in 2018. The Centre maintains that scientists at public- and private-sector research organizations may conduct animal experiments “only if no alternative methods are available, and must do everything necessary to keep the number of animals and the strain that they suffer to a minimum.”

As part of their research on Alzheimer’s disease, scientists at EPFL’s Laboratory of Neuroepigenetics keep the number of animals they use to a strict minimum by taking as many post mortem samples of brain tissue as possible and using data from publicly available databases so they don’t have to repeat experiments that have already been done. “We always calculate our required sample size ahead of time so we don’t use too many animals. And if our initial findings are conclusive and confirm our hypothesis, then we stop the testing immediately,” says Johannes Gräff, who heads the lab.

A range of methods is available to scientists for evaluating their hypotheses, including both in vitro and in vivo tests. “It’s important to understand that you can’t have one without the other,” says the head of the CPG. “Before turning to in vivo tests on animals, scientists first obtain as much data as they can from other methods: in vitro, which are performed on cell cultures, in silico, which are performed using computer models, or organoids, which are a more recent development.” But sometimes, these other methods aren’t sufficient to produce conclusive results. That’s the case for the research being done by EPFL professor Cathrin Brisken, whose lab is studying the role that hormones play in the development of breast cancer. “We simply can’t know what the effects of extended oral contraceptive use are on breast tissue by performing exclusively in vitro tests,” she says. “The data would be misleading because we need to be able to assess the entire body and not just one portion of it.” The experimental protocols used by scientists must therefore be designed to accommodate the strengths and weaknesses of each testing method. The head of the CPG admits that while animal models are very useful, they may sometimes be used inappropriately. “Animal models are not perfect stand-ins for human patients because there are obvious differences between mice and men, for example. But preclinical research can help scientists determine a candidate drug’s efficacy and toxicity before being tested on humans,” he says. “It’s a well-established process.”

We simply can’t know what the effects of extended oral contraceptive use are on breast tissue by performing exclusively in vitro tests”

A heated debate

Animal testing is a sensitive issue and often gives rise to heated debate. The 3R principle can be one way to find common ground, at least according to Fabienne Crettaz von Roten, a University of Lausanne professor and the author of a book titled Expérimentation animale : analyse de la controverse de 1950 à nos jours en Suisse. “People who are opposed to animal testing and scientists are sensitive to the issue and against animal suffering. Both parties agree that the 3R principle provides a way forward, as do efforts to develop alternative methods,” she says. “It’s perfectly normal that the topic is an emotional one – but this reaction isn’t necessarily irrational. We are all affected by animal suffering. But animal testing also provides hope for developing cures to major diseases. The real question to ask is, can we do it better? We need to look at whether our cantonal commissions for animal experimentation are functioning effectively, and whether checks are being carried out correctly. All these are legitimate concerns. It’s good to have a healthy democratic debate on the issue.”

Going forward, it will be important to foster open dialogue between the civil society and the scientific community. Scientific research by its very nature involves continually asking new questions and rethinking existing approaches. The issues we face today won’t be the same ones we face tomorrow, and our relationship with animals is changing thanks to progress in science. By providing transparency on the research processes used by its scientists, EPFL hopes to help inform the democratic debate.

People who are opposed to animal testing and scientists are sensitive to the issue”