In early July, a group of students from EPFL and other universities embarked on a mission to the Moon. Except the six-strong team – three women and three men – never actually left Earth. Instead, the would-be astronauts spent over a week living on a mock lunar base at a top-secret location as part of Asclepios, a project designed by students for students.

The setting for the analog mission was the Grimsel Test Site, a network of tunnels deep beneath the Bernese Alps in western Switzerland. The students met at the foot of a dam before being whisked away by minibus through pitch darkness. Inside, conditions were tough: a steady 13°C, relative humidity above 80%, no natural light – and, of course, no cellphone signal.

A few miles away, another team had converted the gym at Guttannen elementary school into a mission control center. From here, they could keep tabs on what was happening on the base around the clock and stay in constant contact with the crew. As liftoff drew near, everyone wished each other good luck and shared some last-minute words of advice. “We believe in you,” said Chloé Carrière, an EPFL student and president of Space@yourservice, the student association behind the Asclepios mission. “Have a successful mission. See you on the Moon.” After some final hugs, the crew boarded the minibus that would take them deep under the mountain. And on Monday, at 6 p.m. sharp, they closed the door of the base. It would remain firmly shut for a further eight days. Everyone was in high spirits.

Have a successful mission. See you on the Moon”

Before entering the base, the students first had to pass through a decompression chamber. The walls were clad with aluminum panels to make it even more realistic. “The only thing missing was a zero-gravity atmosphere,” said Julien Corsin, one of the analog astronauts. The internal layout was a “do-it-yourself” affair, right down to the dry toilets, which were designed by an architecture student. The two-story base included a kitchen, beds, a lounge, a gym and a tent where the crew could carry out experiments. There was even a curtained-off recess for personal hygiene – because there are no showers on the Moon. “Everything was designed to mimic the conditions in space as closely as possible,” explained Carrière. “The conditions were deliberately extreme, because the idea was to give the crew their first taste of what life is like on a space base.” In all, close to 100 students took part in organizing and running the project. The mission itself involved a crew of six analog astronauts and a 24-strong mission control team to oversee everything.

Lunar mission

Throughout the expedition, the analog astronauts had only limited contact with the outside world: they interacted daily with the control center (strictly for mission-related purposes) but had just five 30-minute Zoom calls with their loved ones. Sophie Lismore, one of the analog astronauts, felt pangs of homesickness during a call a few days into the mission. For Corsin, the hardest part of all was having no Wi-Fi, meaning he couldn’t check his messages on his phone.

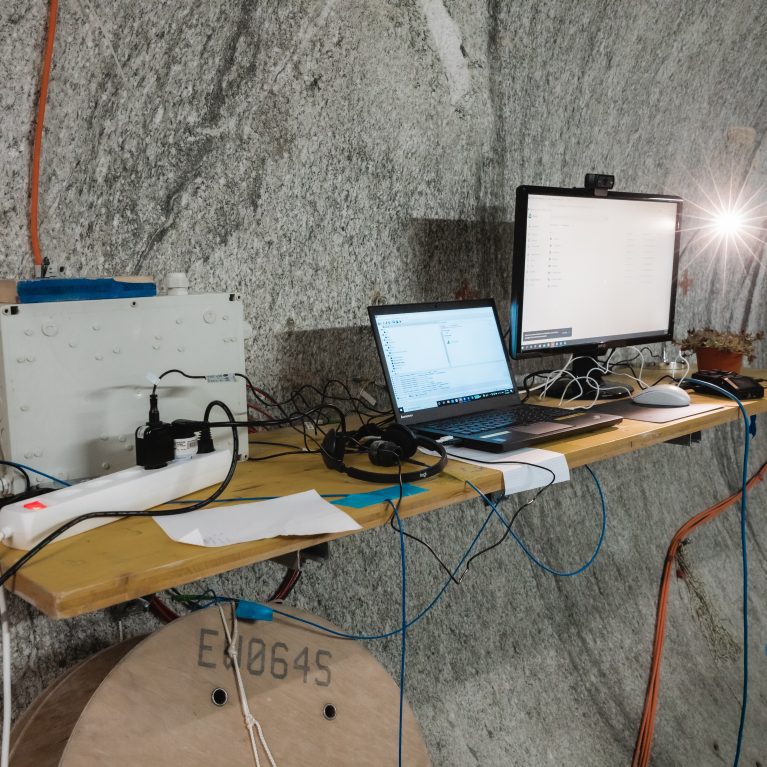

Despite their isolation, the students had a packed schedule. They awoke to the sound of music at 6:30 a.m. each day and went to bed at 10 p.m. Between those times, they had specific tasks to complete: conduct experiments, clean, cook, exercise and record podcasts. And back at the control center, there was a dedicated workstation to make sure the crew were keeping to their regularly updated schedule.

The astronauts had experiments to do every day. On Monday afternoon, for example, they remotely piloted an ice-mining robot developed at MIT to search for water on the Moon. “MIT was eager to test their robot with us because our mission so closely mimicked conditions in space,” said Marcellin Feasson, a physics student and member of the mission control team based at Guttannen. Other experiments included going off-base to carry out topological surveys and making their own band-aids from oil, sugar and cornstarch.

Luckily, none of the crew members seemed fazed by the cramped conditions underground. “We’re all getting along just fine,” said Corsin during a Zoom call. “We have some free time this evening and we’re planning to play board games.” When it comes to being locked up together for eight days, social dynamics seem to make all the difference. “The six astronauts weren’t chosen as individuals but as a group,” explained Carrière. “Their friendship has really blossomed since they met two years ago.” This sense of camaraderie was confirmed by Lismore during one of her calls from the tunnel: “We’re good colleagues, good roommates and good friends. We might be isolated down here, but we’re never alone.”

The six astronauts weren’t chosen as individuals but as a group”

Mission control

At Guttannen elementary school, a clock was hung from the basketball hoop. Two giant screens displayed events in the tunnel in real time, showing the crew members working and preparing their meals. In the middle of the gym, tables were arranged in a U shape to serve as desks. Each station had at least two computers. The flight director – who had overall responsibility for the screens and the data coming from the tunnel – had two laptops, a monitor, three keyboards and three computer mice.

The mission control center ran like clockwork, with students working 24 hours a day in shifts, morning, afternoon, evening and night. Each shift had a color code: blue, green,red and yellow. The atmosphere was studious, like a library, with team members fully focused on the task at hand. The earth communicator (CAPCOM) was responsible for communicating with the crew on the base. The flight planning (FP) team kept tabs on the daily schedule. The flight director (FLIGHT) was in overall charge of the mission control center. And the biomedical engineer (BME) watched over the astronauts’ physical and mental health. The shift changes were seamless, and the focus and concentration were intense. In the evening, those who weren’t on shift grabbed some much-needed sleep. It was a far cry from the hedonism of student parties. “We’ve been preparing for this moment for two years,” said Léonard Freyssinet, a physics student and the mission’s head of communications. “Now it’s finally happening, we want to do it right. There’ll be time to party when the mission’s over.”

The mission control team had plenty to keep themselves occupied when they weren’t on shift. Terence Van Thuyne, a 24-year-old student, took his chess board with him to Guttannen. He spent his afternoons playing against Theodore Bellwald, a physics student who headed up the night shift. “Otherwise, I watch TV shows and play video games,” said Bellwald. Off-duty team members prepared lentil dhal and rice, pizza and toasted sandwiches for on-shift colleagues in the communal kitchen. Others made their own meals. They spent their nights in the nuclear fallout shelter beneath the school. With no windows and no heating, conditions were just as uncomfortable as on the base itself. “Except we have thicker mattresses,” said Freyssinet.

At 10 p.m. on the final night of the mission, the sound of voices and piano playing could be heard coming from the school’s music room. A group of students had decided to record a song for the astronauts’ final wake-up call the next morning. Jessica Studer, a medical student and the mission’s medical officer (MEDOPS), and Elfie Roy, an EPFL physics student and assistant project leader, were performing a duet.

I watch TV shows and play video games”

Back in the gym, biomechanics student Loïc Lerville was at his post, ready to make the final evening call to the team on the lunar base. He’d planned to read an excerpt from The Little Prince to crew commander Eleonore Poli, altering some of the wording to make reference to the mission. “She forgot to take something to read with her,” explained Lerville. “So I read her a passage from a book every night. It became our little ritual.” Poli could be seen listening intently on the screen.

Back to Earth

At 7:30 a.m. on Tuesday, the mission control center was buzzing with activity: Van Thuyne already had his chess board out and it was time for the final briefing. The tired faces of the astronauts appeared on screen. The mission control team zipped through the day’s schedule: exercise, cleaning and tidying, liftoff and return to orbit. The CAPCOM signed off the briefing: “Enjoy your last day on the Moon.”

At the end of the day, the landing (or rather, the return trip by minibus) went off without a hitch. The six crew members, all safe and sound, were greeted at the control center by a guard of honor, rapturous applause and a final word from Carrière: “Thank you for making this dream come true.”

Website: https://asclepios.ch/