Until 2003, there was no one central location for outer space at EPFL. There were some professors working on different research related to space, and students working on space-related projects, but there was no one place or program where they could meet, collaborate, and grow.

Then in 2003, EPFL and RUAG Aerospace decided to set up the Space Center at EPFL to develop R&D, technologies, and applications related to space at EPFL. In 2004, they were joined by the Swiss Space Office. Over the last 20 years, the EPFL Space Center has gone through many names and iterations, but the mission remains: foster, promote and federate space technology and science across education, science and industry at EPFL as well as across Switzerland and internationally.

One of EPFL’s longest-running Centers, the EPFL Space Center has helped send technology into space, created and ushered over 450 students through the Minor in Space Technologies, managed space-related student teams, and led the charge in the important emerging field of space sustainability, with research projects and successful spinoffs.

- “It’s our job to think about how to make space missions more sustainable”

- EPFL in outer space

- EPFL’s student space teams

- “Right now, there is a kind of renaissance in space”

- Contributions to international space science

Space at EPFL today

Composed of two units – eSpace, which covers research and education, and Space Innovation, which works with space industry – the EPFL Space Center, federates much of the space-related activities that take place on campus.

The Center supervises and coordinates six space-related student projects as they win international awards and competitions and send technology into space, runs the Minor in Space Technologies, and hosts master’s and PhD students for their thesis work. The Center also works to connect professors across campus from over 40 laboratories who do research related to space to collaborators and members of industry, and maintains a network of organisations active in space from academia and industry across the country,connects them with one another, and provides resources they can use. And in terms of advocacy and outreach, they host international aerospace events and work with policymakers on issues of space sustainability.

As space science and the space industry continue to grow significantly, the role of the EPFL Space will continue to grow and change as well to meet the evolving needs of the community it serves.

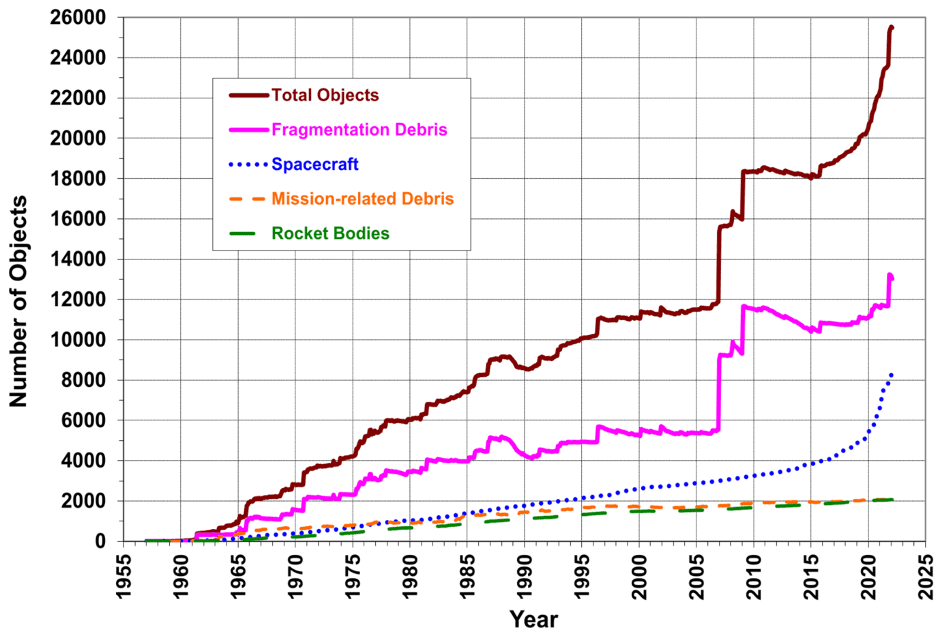

There are currently around 3,400 operational satellites in space, with plans to launch up to 50,000 more in the next decade. Many of these will make up large satellite constellations that provide telecommunication services. However, each additional item put into space increases the risk of collision and the potential generation of new pieces of space debris, the name given to any non-functional object in space. This proliferation threatens the capacity of Earth orbit to safely accommodate new objects.

The EPFL Space Center has been working on this problem for over a decade, starting with the CleanSpace One project, which became the startup ClearSpace, along with the Space Sustainability Rating and research projects for national and international partners.

“It’s hard to overstate the importance of sustainable thinking at a time when we’re seeing ever more traffic in orbit,” says Emmanuelle David, Executive Director of eSpace, the education and research unit of the EPFL Space Center. “As a research center with deep expertise in this field, it’s our job to think critically about these changes and the technologies and policies needed to make space missions more sustainable.”

EPFL’s hub for sustainable space

EPFL’s research activities around sustainable space take place within the EPFL Space Center’s Sustainable Space Hub. This hub operates a number of projects that work with space agencies, academia, and industry.

From 2019 to 2021, the EPFL Space Center managed the Research Initiative for Sustainable Space Logistics (RISSL), a large project funded by the Swiss Space Office, that worked on issues of active debris removal and mission optimization.

Since then, as part of an ESA project on Green Space Logistics, engineers and researchers at the Sustainable Space Hub have been working on the Technology Combination Analysis Tool (TCAT) tool, which performs space logistics optimization, and the Assessment and Comparison Tool (ACT), which is made to perform rapid life cycle assessment of future space systems. The ACT is intended to be used in early design phases, to screen expected environmental impacts and hotspots, and support the first ecodesign efforts in a space mission. In 2023, a new project with ESA began the second project phase to improve and deploy ACT.

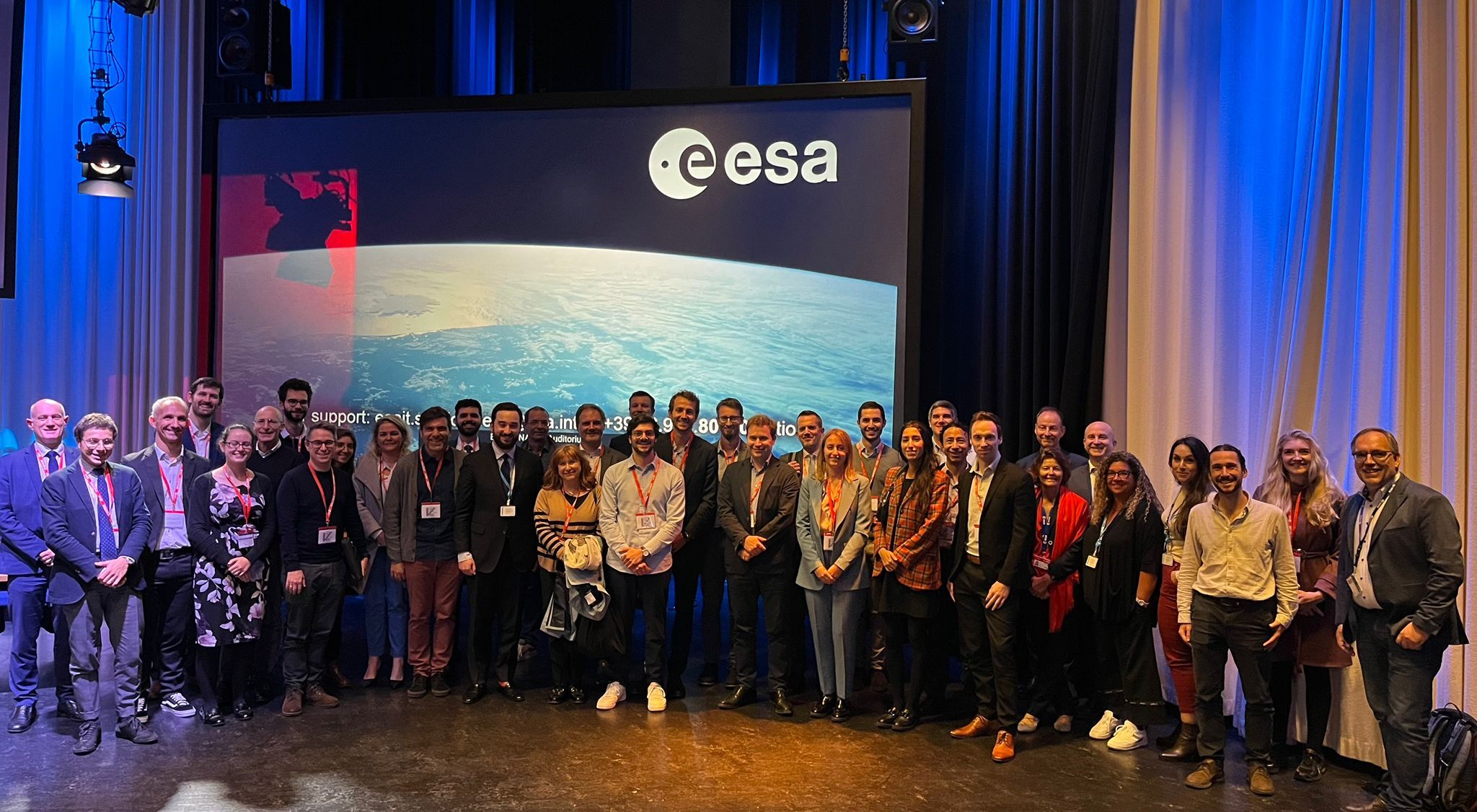

Members of eSpace and the Space Sustainability Rating attending the ESA Clean Space Industry Days, one of most important space sustainability events in Europe © ESA

Also in 2023, the project, “Space sustainability: Policy options and interrelations with Earth system governance”, led by senior researcher Xiao-Shan Yap, began at the EPFL Space Center. This project will provide evidence-based insights to policy-making and link with the Space Sustainability Rating, another of EPFL’s startups related to space sustainability.

’We are living in an era in which ensuring earth-space sustainability will be a rising challenge. Mismanagement of increasing space activities not only threatens the long-term functions of space-based infrastructures for daily activities on Earth, it causes environmental consequences to the Earth system, undermines ongoing sustainability transitions, and exacerbates global inequality,” says Yap.

’We are living in an era in which ensuring earth-space sustainability will be a rising challenge.”

– Xiao-Shan Yap

Spin-offs to clean up

In early 2018, EPFL Space Center researchers founded the ClearSpace startup to pick up where the Cleanspace project left off. The startup’s first debris-clearing space robot was designed to de-orbit SwissCube, a Cubesat launched into orbit by EPFL and its partners in 2009. The company then won a ClearSpace-1 mission contract with ESA in 2019 to remove the Vespa Upper Part of the 2013 Vega rocket. In early 2023, ClearSpace successfully passed their first major program review (KPG-1) with the European Space Agency (ESA) for its ground-breaking mission to remove a large debris object from Earth orbit. The company also raised €26 million from Series A financing round to further accelerate the movement toward the sustainable use of space. The ClearSpace-1 mission is nominated as one of the TIME Inventions 2023.

The EPFL Space Center also hosted another spin-off, the Space Sustainability Rating (SSR). In 2021, the EPFL Space Center was selected as the host of the: SSR a voluntary rating system to incentivize sustainable behavior in space, developed by a consortium including the World Economic Forum (WEF), ESA, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), BryceTech, and the University of Texas at Austin.

The SSR is a voluntary rating system providing space actors with a simple and impactful instrument measuring the sustainability of the design and operations of their missions. Ratings range from bronze to platinum, giving spacecraft manufacturers the ability to obtain transparent and data-based assessments of the level of sustainability of their missions. The SSR also identifies areas where improvements can be made, and supports publicly sharing the rating’s outcomes, allowing rated organizations to communicate their efforts towards space sustainability. The SSR spun-off from the EPFL Space Center in June 2023, becoming its own non-profit association.

Artistic impression of the servicer ClearSpace-1 approaching the space debris object VESPA during the ClearSpace-1 mission to take place in 2026 © ClearSpace

Going forward, the EPFL Space Center will increase its commitment to space sustainability, by fostering collaboration between laboratories and projects within EPFL and Switzerland.

EPFL space spinoffs

Astrocast: A nanosatellite company focusing on providing global Internet of Things (IoT) connectivity through its Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite network.

Bcomp: A materials technology company specializing in developing innovative and sustainable lightweight composite materials for applications in industries such as aerospace.

ClearSpace: A startup specializing in space debris removal, developing technology to address the growing issue of orbital debris in Earth’s vicinity.

CompPair: Technologies: A materials science company specializing in self-healing and composite material repair technologies, enhancing the durability and longevity of various materials in industries such as aerospace.

DPHI Space: A company that offers ridesharing solutions for hosted payloads to accelerate access to space.

Picterra: A company specializing in artificial intelligence and geospatial analysis, offering a platform for the automated analysis of satellite and aerial imagery.

Space4Impact: An organization that promoted space technologies that have a positive impact on Earth (now closed).

Space Sustainability Rating: A comprehensive rating system designed to evaluate and promote responsible and sustainable behavior in space activities.

Swiss to 12: A company specializing in advanced 3D-printed radio frequency (RF) components and antennas for space, telecommunications, and defense applications.

The Countdown Company: A company offering tailored engineering solutions to meet tight deadlines and speed up engineering project development cycles.

ViaSat Antenna Systems: A global broadband services and technology company that designs, integrates and delivers secure, high-performance satellite and wireless services.

In 2009, the EPFL-built cube satellite SwissCube was launched into space. And over a decade later, in 2023, EPFL returned to space thanks to the EPFL Spacecraft Team and their on-board computer, Bunny.

SwissCube: The ultimate survivor

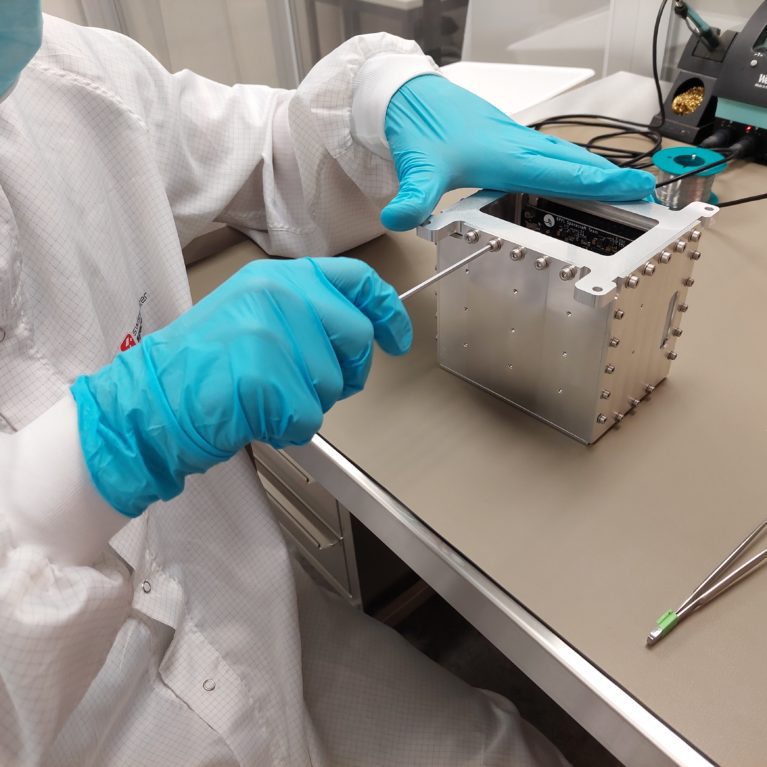

The SwissCube project was initiated in 2005 by the EPFL Space Center and the Microsystems for Space Technologies Laboratory (LMTS). It was a multi-level research project with teams for each facet: dynamics, telemetry, ground station, solar energy, among others. During the years that the SwissCube was being engineered and built at EPFL, over 250 students had the chance to be part of the project.

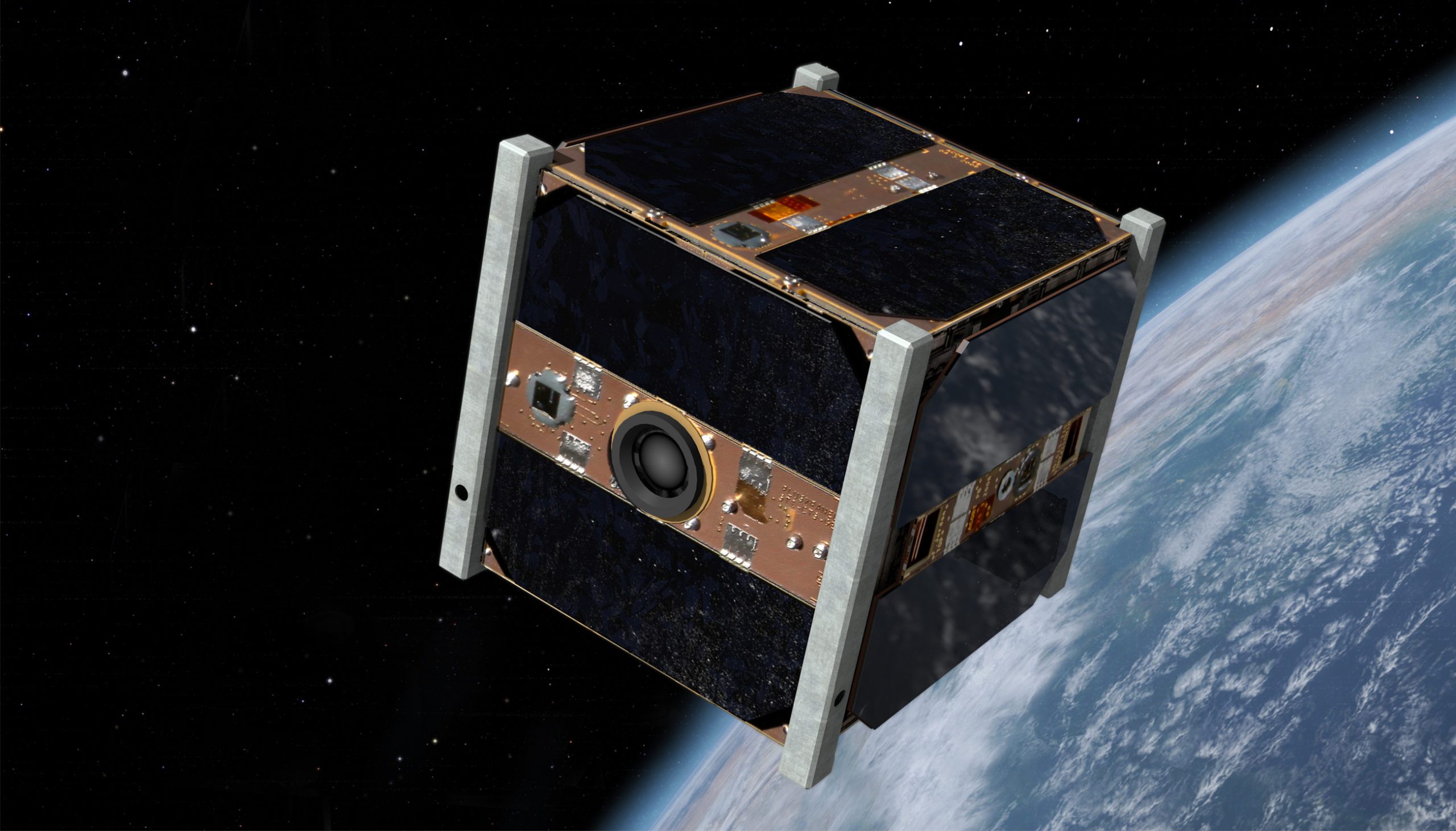

SwissCube was a collaboration between EPFL, the University of Neuchâtel, HES-SO, and FHNW. Its primary goal was educational; to show students how to build a complex engineering system from A to Z. Though the satellite is rather small in size, a cube with sides of 10cm for a weight of less than 1 kg, it contains all the critical sub-systems and functions present in larger satellites.

The EPFL satellite was launched by the Indian space agency (ISRO) in September 2009. Initially, it was intended to perform a nine-month mission but amazingly, it is still sending telemetry today – making it one of the oldest in the history of surviving cubesats.

“What people may not remember is that in 2009, the satellite industry was not yet established. The rate of success was something like 30%,” explains Anton Ivanov, former EPFL Space Center researcher and current Director of the Propulsion and Space Research Center of TII, Abu Dhabi.

“In the beginning, SwissCube was spinning so fast that we couldn’t send a command! Then we had to reset it, and the only way to do that was to drain the battery and wait for a reboot. So we figured out how to do that, and we got the first picture. Everybody was so happy!”

Armin Rösch, a CFF radio platform manager from Deitingen, remembers this well. He connects to SwissCube in his spare time, and since the telemetry began, he has been downloading and publishing it online.

“We expected a short lifespan because of batteries,” Rösch explains. “They are standard batteries like in a mobile phone. Yet the battery still works. Whoever wrote the battery management software did a great job!”

SwissCube also dodged a bullet: it was initially intended to be the target of the ClearSpace mission, to remove space debris, but when European financing arrived, it was for debris from an ESA launch instead.

Next year, the EPFL Space Center, Rösch and many others hope to celebrate the 15th year of Swisscube’s nine-month mission.

The Bunny: bringing EPFL back to space

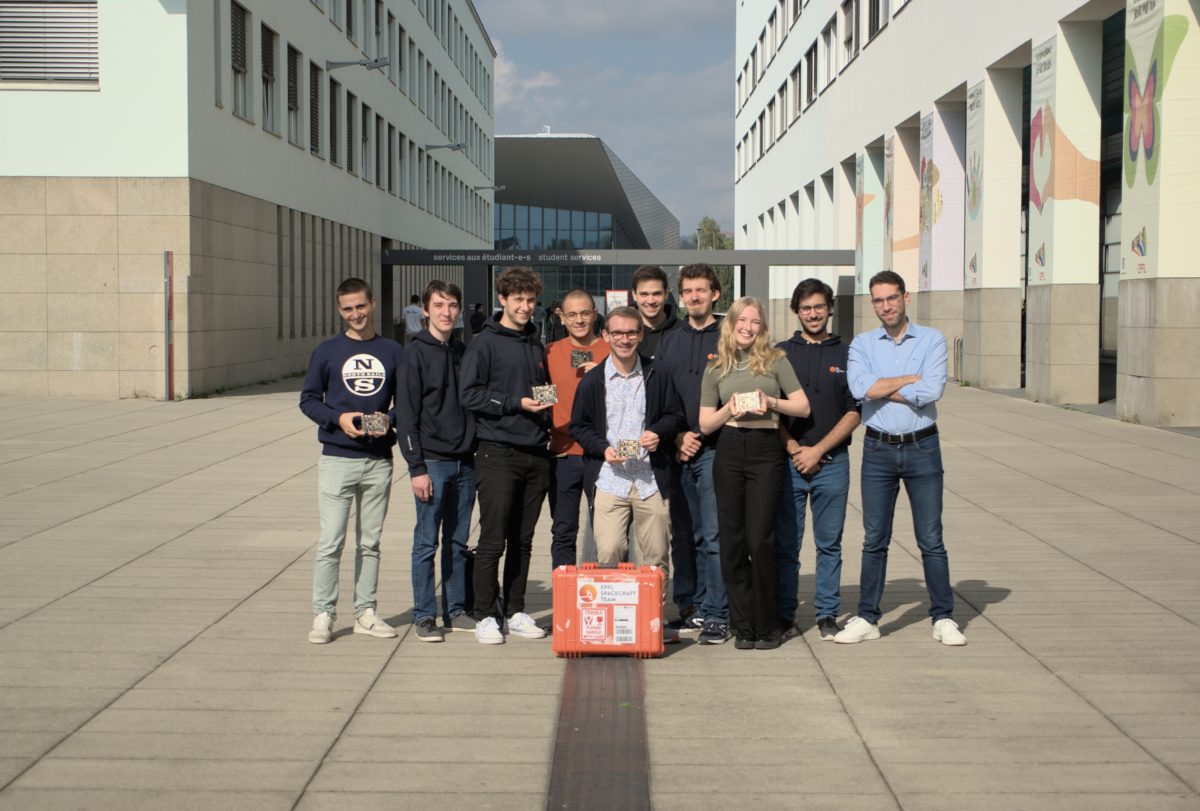

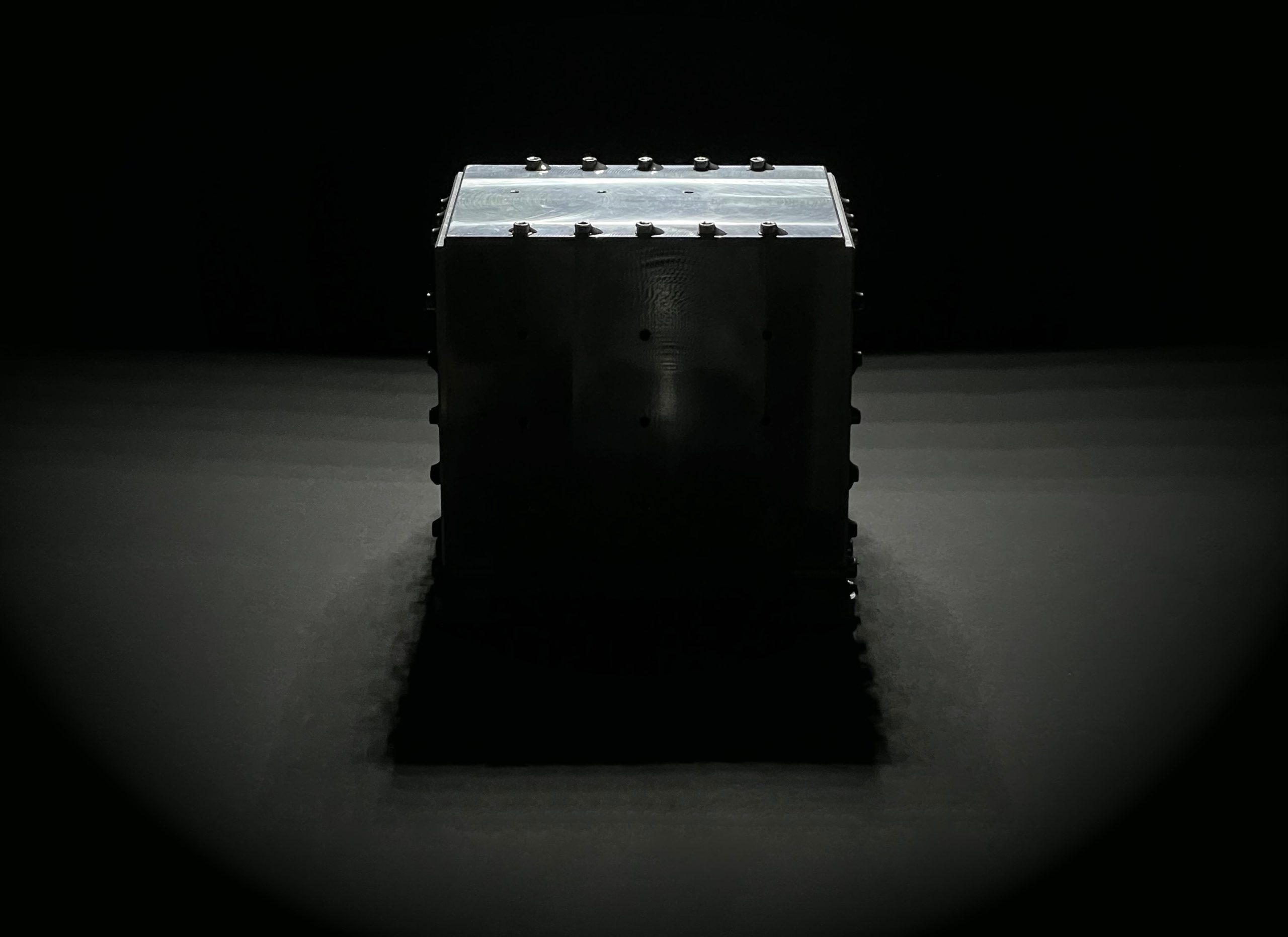

Nearly fifteen years after the launch of the SwissCube, another piece of EPFL technology went into space in 2023: an onboard computer named Bunny, built and designed by the student-run EPFL Spacecraft Team leading the CHESS mission. The aim of the CHESS Mission is to build and launch two CubeSats, miniature satellites in 10x10x30cm cubes, in 2026 and 2028, and Bunny is a prototype of the onboard computer for the CHESS mission.

Initially, the team had been solely focused on their 2026 launch, until April 2022 when the Italian aerospace company D-Orbit came to them with the opportunity to fly their computer on an experimental mission inside an ION Satellite Carrier in January 2023.

“We didn’t really know how to go about this process because we weren’t that far ahead in the mission,” says Robin Bonny, who was Vice President of Electronics for the EPFL Spacecraft Team at the time. “But we always had the onboard computer, the only system that was fully developed by EPFL students at that time. So we decided to take the design that we had and get it to fly as soon as possible.”

As the CHESS is a long-term project, the current EPFL Spacecraft Team students mostly won’t be at EPFL anymore by the time it launches. Working on the on-board Bunny computer gave current students a chance to experience the real-world experience of building and qualifying something to be launched into space.

“We decided to take the design that we had and get it to fly as soon as possible.”

– Robin Bonny

Bunny’s mission concluded in July 2023 at the end of the planned operational phase of six months. During this period, Bunny continued to respond to uplinked commands and most of the tests that the team ran. The success of Bunny led to the kick-off of the development for the next in-orbit demonstration/validation: the X-band transmitter and next-gen onboard computer – Bunny’s successor, called TwoCan. The goal is to fly these subsystems jointly by the end of 2024, to validate their performance in the low-Earth orbit environment, and to establish contact with the ground station on the roof of the ELB building at EPFL.

In 2023, the EPFL Spacecraft Team also won Space Universities CubeSat Challenge 2.0 (SUCC) out of 75+ applications with another Chinese Student Team from Beihang University. This gives them the possibility to launch their first satellite CHESS Pathfinder 1 for free on a Chinese Launcher in 2026.

Going forward, the Spacecraft Team hopes to operate a project similar to Bunny each year, so that all student members go through this process of developing and qualifying something for space within one year.

“It seems like a logical progression that the SwissCube was more than 10 years ago, and now we are leveraging this heritage and showing that we as a team of students can go up in complexity,” says Bonny.

These projects give students the opportunity to engineer and build technologies aimed for outer space, simulate a mission on the Moon, and share their passion for the cosmos with others.

The EPFL Rocket Team: Founded in October 2016, the EPFL Rocket Team brings together motivated and passionate aerospace enthusiasts. This interdisciplinary student initiative was born following the desire of many students from different engineering faculties to put into practice their accumulated knowledge, The team has more than 80 active members. In 2021, they won the European Rocketry Competition (EuRoC) with their rocket Bella Lui II , and in 2022 they came in third with the rocket Wildhorn. At EuRoC in 2023, they launched the first Swiss-made bi-liquid Rocket.

The EPFL Spacecraft Team: The EPFL Spacecraft Team is an association for motivated students who want to be part of ambitious space projects. The objective is to perform scientific research with satellites developed by students. Their first mission called CHESS Pathfinder 1 is a 3U CubeSat which is going to measure the chemical composition of the Earth’s atmosphere. Therefore, it will host two scientific payloads from the University of Bern and the ETHZ. The students at EPFL are responsible to develop and test the platform. In January 2023, a first in-orbit demonstration of the on-board computer Bunny was launched into space with D-Orbit.

EPFL Xplore: EPFL Xplore is a student-led space robotics project from EPFL, part of the MAKE initiative in Switzerland. They build rovers to participate in international competitions such as the annual European Rover Challenge. The team won 3rd place overall at the on-site edition of the ERC 2021, 2nd place overall at the ERC 2022 and 3rd place again in 2023. It was also awarded excellency awards for the navigation, science, and probing and collection tasks.

Space Situational Awareness Team: Founded at EPFL in 2020, the Space Situational Awareness (SSA) EPFL Team aims at creating and maintaining a catalog of objects orbiting the Earth to predict collisions with existing satellites and ease space development. Their medium-term goal is to be able to track and identify most of the objects and debris in orbit that are visible from the ground.

Space @your Service: Space@yourService (S@yS) is an EPFL association whose main goal is to promote and popularize space sciences (astronomy, astrophysics and space engineering) among the general public and EPFL students. They organize events open to everybody and accessible to anyone, such as the Astronomy on Tap in local bars in Lausanne. They are also the owners of a SciComm mobile escape room.

Asclepios: Asclepios was created by a group of EPFL students to simulate a mission to the moon using the former military fortress of Sasso San Gottardo as a “lunar base”. It is the first initiative worldwide of a space simulation mission created completely by students, for students, in collaboration with academic institutions, scientists as well as industry.

Callista: Callista’s objectives are to promote interest in astronomy at the university sites of EPFL and UNIL by several means. On the other hand, for more motivated people, the possibility of studying certain subjects in depth in the framework of presentations and scientific projects intended for members of the club, or the possibility of making more specific astronomical observations.

Gruyère Space Program: The Gruyère Space Program is a student association composed of five EPFL students developing the world’s first student-built rocket hopper. Since 2019, they are gaining experience in the scope of stabilized rockets and are now developing the first student-built rocket able to take off and land vertically (VTVL). In 2023, Colibri, their bi-propellant vertical takeoff, vertical landing (VTVL) rocket, performed its first flight, demonstrating their ability to implement this advanced technology, used for launcher reutilization and interplanetary landers.

During his time at EPFL, Krpoun was part of the SwissCube project and worked with Claude Nicollier to help create the first courses that eventually became the Minor in Space Technologies. Here he discusses the trajectory that took him from EPFL all the way to the Swiss Space Office at the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation, and how he sees the future of space research and education.

What was space education like when you were at EPFL?

When I started in 1998, there was basically no space curriculum at EPFL. There were some professors who were working on different space issues: Pénélope Leyland, who was working on high-speed aerothermodynamics and had been on the ESA Hermes project, Juan Mosig, who was very active in antenna design, and Yves Perriard, who made his laboratory available for hands-on related space projects. In terms of the students, we started with a project, the Student Space Exploration and Technology Initiative (SSETI) from ESA. This eventually grew into SwissCube, thanks to the initiative of Herbert Shea.

After EPFL, what was your trajectory to get to your position today?

First, I was at CSEM in Brazil, then back to RUAG Space (today Beyond Gravity) in Switzerland. I worked on ExoMars and the Small GEO satellite, both ESA projects. My final assignment for RUAG Space was in Alabama, leading the development of a factory. In 2016 the opportunity had just opened up to lead the Swiss Space Office. I applied and got the job, and this is how I ended up working more in governmental issues. For about six-and-a-half years, I had the privilege to head the Swiss ESA delegation. And then in spring 2023, I was appointed by the ESA Council at the delegate level as its Chair, which is where we’re at today.

How did your education at EPFL help prepare you for your space career?

EPFL is an amazing place. Not only will you get the solid technical, scientific background and rigor, but you also have the opportunity to do hands-on learning. There was a lot of support from the professors to go into the SSETI project and build a satellite, and then we got the support and funding to do SwissCube. That really prepared me not just to have a theoretical, but also a more practical background, which is still important for me today, because when we discuss certain issues in the ESA Council, there are also a lot of technical aspects. It helps me for useful input when it comes to making smart decisions.

EPFL is one of the best engineering schools in the world. With what you learn and the tools you get, you are well prepared to take the lead on projects. This is what makes it like a leadership school, which I think gets too often forgotten when we talk about EPFL.

Why is it important to have a Minor in Space Technologies at EPFL?

Why would we not look at space? I know some people think that investing in space is just about prestige. But at the end of the day, there is a necessity to understand what’s going on around us. It would be like living on an island and saying that you don’t care about the ocean.

There are also a lot of economic opportunities. The space economy has been growing about 9-10% a year worldwide. We see that space is taking a more important role within our daily lives, with, for example, meteorology, navigation, telecommunication. And there is this high-tech environment that we have in Switzerland, the sense of quality, that fits very well with space, because if you’re in space and something breaks, you usually cannot repair it – unless you can send up Claude Nicollier.

What do you hope to see in the future in terms of space education at EPFL?

It’s not really my place to give EPFL any tips, but perhaps this one: Right now, there is a very dynamic space ecosystem in the Lausanne region, but EPFL lacks a bit of critical mass because there are not many professors working in the space field. It would be great to have more professors for teaching and researching and exchanging on that. Maybe to join forces with what Thomas Zurbuchen is doing in Zurich. If you look at the student associations, there’s a lot of interest in space.

What advice for the next generation of space students and space professionals?

Space is undergoing major changes right now. First of all, there’s a retirement wave as many space engineers are leaving, so there is kind of a renaissance. You have many new talents coming into the space ecosystem and many new opportunities. We’re moving towards more human spaceflight. We’re currently discussing what we can do after the International Space Station gets retired. Humanity is going back to the moon and we’re engaged in the Artemis program through ESA; there are many exciting things to be done. Switzerland has become more active and more visible, and as a partner we are becoming more attractive.

Thanks to the contributions of EPFL scientists, society has seen amazing pictures of our solar system and gained a better understanding of the nature of the universe.

Helping construct the largest radio telescope

With its secretariat at the EPFL Space Center, the Square Kilometer Array Switzerland (SKACH) consortium is the Swiss arm of the international Square Kilometer Array Observatory (SKAO), a next-generation radio astronomy facility that will revolutionize our understanding of the Universe and the laws of fundamental physics. Through SKACH, ten national academic institutions are providing leadership in multi-disciplinary efforts to be at the forefront of space science in Switzerland.

Currently under construction, when they come fully online, SKAO telescopes in Australia and South Africa will look as far back as the Cosmic Dawn, when the very first stars and galaxies formed. By several measures, SKA will be the largest scientific facility built by humankind and with an expected operational phase of at least half a century, it will be one of the cornerstone physics machines of the 21st century.

Switzerland has committed more than 33-million CHF to 2030 towards the construction and early operation of the telescope, which will collect unprecedented amounts of data, requiring the world’s fastest supercomputers to process this in near real time. Swiss researchers will be fundamental in processing the data (~650 PBytes/year) generated by the SKA telescopes in areas such as astrochemistry, galaxy surveys, dark agesand cosmology.

“Through SKACH, the EPFL Space Center has helped to create a truly national, multi-disciplinary hub for space research,” says Prof. Jean-Paul Kneib, Swiss Scientific Delegate to the SKAO Council. “From computer science to astrophysics and cosmology, SKACH is ensuring that Switzerland is punching above its weight in this extraordinary international consortium.”

Revealing the nature of Dark Matter

The ARRAKIHS (Analysis of Resolved Remnants of Accreted galaxies as a Key Instrument for Halo Surveys) satellite was selected by ESA to address the nature of dark matter, and will be launched in 2030.

Pascale Jablonka of EPFL’s Laboratory of Astrophysics (LASTRO) leads the science component of ARRAKHIS, which in September 2023 just successfully passed the mission definition review of the project, a very important first milestone towards full completion of the mission preparation which gives the ARRAKHIS consortium and the ESA study team the green light to move forward to the next phases of the project.

“We are very excited! It’s a happy and emotional moment to get past this first phase. It means that the mission is now concretely valued. We are entering an even more active phase of the project, for which we need support from the national agencies,” Jablonka explains.

“Through SKACH, the EPFL Space Center has helped to create a truly national, multi-disciplinary hub for space research”

– Jean-Paul Kneib

Observing the darkness of the Universe

EPFL is also part of ESA’s Euclid space mission, which in November 2023 revealed its first full-colour images of the cosmos. Never before has a telescope been able to create such razor-sharp astronomical images across such a wide patch of the sky, with both a visible camera and an infrared spectro-imaging camera.

Switzerland and a number of Swiss institutions are part of this revolutionary space mission that will map Dark Matter in the Universe. At EPFL, Professors Frederic Courbin and Kneib are contributing by designing the pipeline to find strongly lensed systems and through the strong gravitational lensing measurements, addressing key questions regarding the distribution of dark matter, galaxy formation and evolution, and cosmology.

Understanding the first galaxies

Since reaching Lagrange Point #2 and successfully deploying its mirror and seven-layer sun shield, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has revealed gorgeous infrared images of distant galaxies. Although EPFL did not participate in the construction of the JWST, its scientists have participated in the preparation and evaluation of science projects to be conducted with this telescope.

The first image revealed in July 2022 was scrutinized by an international team of astronomers including Prof. Jean-Paul Kneib, and led to the first scientific paper of JWST modeling a massive lensing cluster and identifying the most distant galaxies in the Universe.

“Prior to its launch, I had been constructing emission-line catalogues of the first galaxies in order to characterize them. With the new impressive JWST data, I can finally use my tools with my team to interpret the data and better understanding the evolution and formation of the first galaxies in the young Universe” explains Prof. Michaela Hirschmann, head of the EPFL Laboratory for Galaxy Evolution and Spectral Modelling (GALSPEC), who is using JWST data for her research.

Other EPFL astrophysicists in the group of Prof. Frédéric Courbin are studying lensed quasars in detail, and others in the group of Prof. Richard Anderson are monitoring SuperNovae and Cepheids. Both groups aim to measure the Hubble Constant with improved precision using two complementary different techniques.