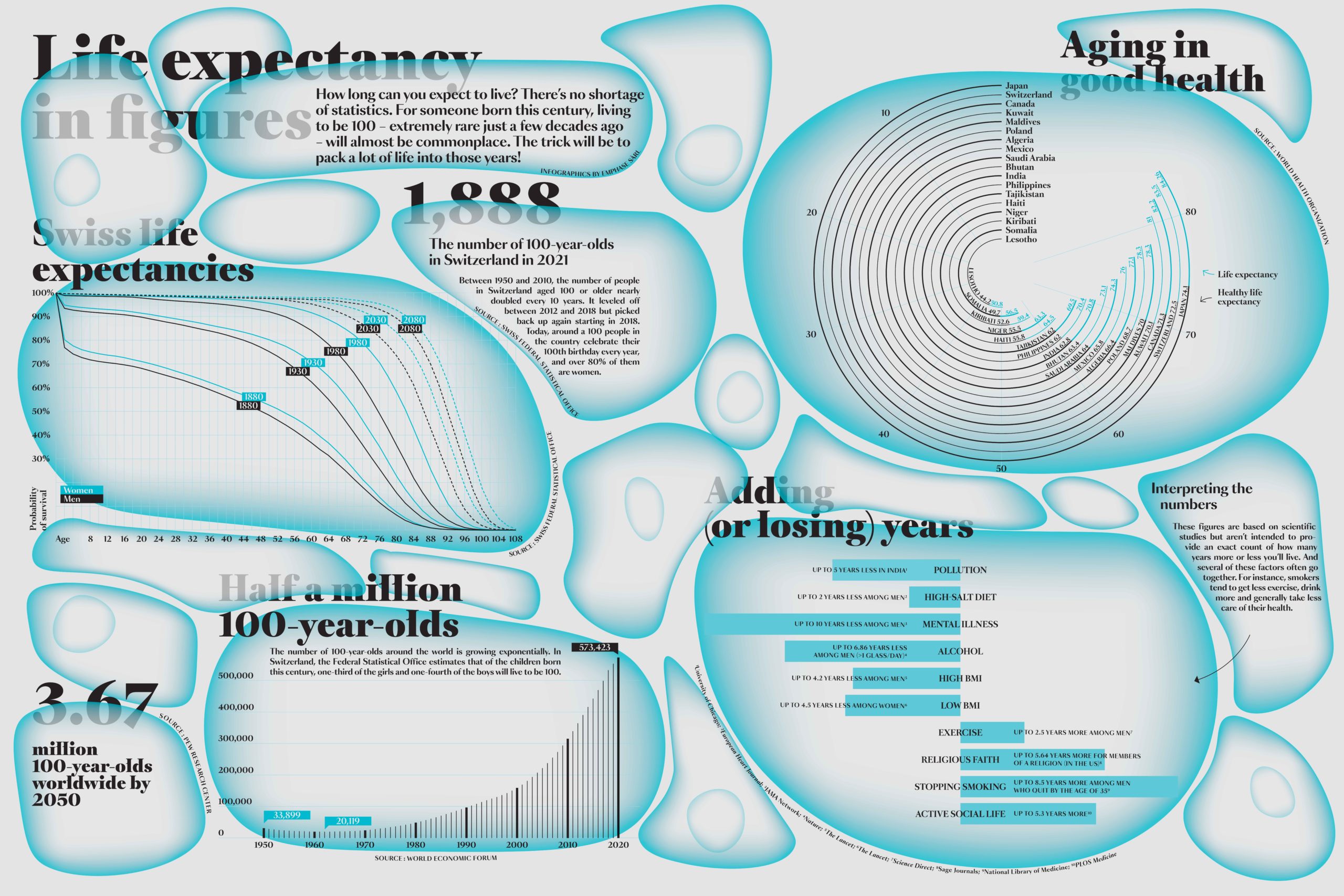

Hawkers of miracle cures and fountains of youth exhort you to “add life to your days and not days to your life.” Nowadays, a growing number of scientists are picking up that refrain. They’re looking at how we can remain in good health as long as possible given the obvious benefits in terms of wellness, social inclusion and economic participation. And they’re taking what seems to be the most sensible approach: seeking to delay the end of people’s “healthspan” – the point at which their quality of life decreases and their need for medical care increases – and to shorten the relative length of that final phase of life marked by serious health issues.

Today’s aging society is forcing us to rethink some very fundamental questions, such as whether the working population will be able to fund retirees’ social security benefits; what the best elderly-friendly approaches to urban planning and architecture are; how to redefine the individual’s role in society depending on their state of health; how domestic robots can be a boon for the elderly; and the ethically thorny issue of whether there’s an “expiration date” on human life.

- New strategies aim to prevent the onset of disease

- Mice are essential models for understanding the aging process

- Prescriptions for living a longer life

- Technology can help seniors stay independent for longer

- Women have the edge

- Tell me where you live and I’ll tell you your life expectancy

- Putting an end to agism

- “When we’re with people we love and have a meaningful life, we want to live forever!”

We’re not all equal before old age. A number of factors – including genetics, our environment, our lifestyle and the food we eat – affect how healthy we are and whether we develop a major age-related illness. “We need to make a distinction between our lifespan – the number years we live – and our healthspan – the number of years we live in good health,” says Johan Auwerx, the head of EPFL’s Laboratory of Integrative Systems Physiology (LISP). “Treatments have been developed, such as for cancer, that can extend our lifespan, but they mainly extend the years during which we struggle with health issues. The average life expectancy in Europe is 79 years, but the average healthspan is just 68 years. Those 11 years – and especially the last one – tend to be very difficult, whether in terms of the quality of life of the individuals and their loved ones or the costs of the necessary care. These costs are generally borne by society through health-insurance systems.”

Taking a healthspan view would require rethinking our approach to medical research. “Scientists today are still very rooted in a ‘treatment’ paradigm, where the goal is to address diseases as they appear,” says Auwerx. “But thanks to technological advances, we’ll soon be able to nip those diseases in the bud – that is, intercept them before they occur. This will bring clear benefits in terms of quality of life and costs.”

Many strategies are being explored to reach that goal. The most scientific are based on defining what it really means to age and, most importantly, pinpointing the factors that lead to the development of certain diseases. “DNA tests are already commercially available that, for just a few dollars, can tell you if you have a genetic predisposition to develop a specific disease,” says Auwerx. “If so, you can take the necessary steps towards prevention through a genuinely personalized approach.” He cites the example of Angelina Jolie, who underwent a double mastectomy and had her ovaries removed after finding out she carried a mutated gene.

Not everyone needs to take such drastic measures after discovering a genetic predisposition – there’s a whole range of preventive options out there. A vast study conducted in Iran (PolyIran, published in The Lancet in 2019) found that giving participants low, targeted doses of standard low-cost drugs starting at the age of 40 significantly reduced the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. These individuals are much less likely to have to take dozens of pills a day when they reach their 60s. “The tendency to prescribe a slew of medications to seniors – known as overprescription – doesn’t work and isn’t viable over the long term,” says Auwerx. “But it’s become standard practice in the West for people above a certain age.”

The tendency to prescribe a slew of medications to seniors – known as overprescription – doesn’t work and isn’t viable over the long term.”

Another way to intercept diseases is to adopt a healthy lifestyle, such as by eating right and getting regular exercise. These kinds of lifestyle factors play a crucial role in extending our healthspan. Data clearly show that for most people, their health tends to decline rapidly after retirement. Auwerx explains: “The key is staying active. We also have systems now that can combine genetic data with real-time health parameters measured by smart watches and other connected devices. This is a booming field, and it means we’ll soon be able to intercept more and more diseases before patients start needing treatment.”

That’s the idea behind the Healthspan Diversity Project, which Auwerx and his research group launched in 2018. They’re studying the factors that influence longevity in mice and comparing this information with clinical data on cohorts of human patients. The goal is to be able to apply their findings on mice to humans.

Healthspan research is still in its early stages but a growing number of scientists are getting involved and tackling some of the most basic questions. For example, when can we say a person’s healthspan has ended and they’re living the remaining years of their lifespan? Once that point has passed, can they return to living in good health, such as after recovering from illness? And if doctors are able to extend patients’ healthspan, does that mean we should raise the retirement age? Finding compelling answers to these and other questions will become increasingly important as senior citizens make up a growing share of our population.

Is old age a disease?

If all goes well, we’ll all be old one day. But scientists are still divided on what exactly it means to “get old.” A study published in Cell ten years ago identified nine hallmarks of aging that can be used to observe and even measure the mechanisms causing our health to decline as the years go by. This past January, the authors updated their findings and added three more hallmarks, bringing the total to 12: genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, disabled macroautophagy, deregulated nutrient-sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, altered intercellular communication, chronic inflammation and dysbiosis.

“Each of the hallmarks should be considered a point of entry for the future exploration of the aging process, as well as for the development of new antiaging medicines,” they state in the paper.

While these hallmarks have the benefit of letting us objectively assess specific aging processes, they don’t give black-and-white answers. What’s more, Auwerx points out that they encourage us to look at factors in isolation when they should be examined holistically. “Aging is above all a steady deterioration in all our biological functions,” he says.

Some scientists believe we should consider aging itself to be a disease so that clinical trials can be run to examine methods for slowing the process. That’s the view held by Jean-Marc Lemaitre at France’s INSERM research center, who recently wrote that we could one day “treat” aging, such as by transforming senescent cells into stem cells. “If we want to treat aging with drugs and molecular compounds, we’ve got to be able to consider it a disease,” he says. “That’s not the case today and it’s creating problems for doctors.”

But from an ethical standpoint, is it acceptable to use drugs to treat or prevent aging? Andrew Steele , the author of Ageless: The New Science of Getting Older Without Getting Old, doesn’t see why we shouldn’t take advantage of antiaging therapies. “There’s no real evidence that the extra years bought by preventing heart attacks have stripped modern life of its meaning – so why would adding a few more years free from heart attacks and cancer and frailty do so?” he says.

Scientists today are still very rooted in a ‘treatment’ paradigm, where the goal is to address diseases as they appear.”

Although mice and men don’t appear to have much in common, the small rodents have been instrumental in a number of important biomedical breakthroughs. Over 90% of human genes are the same as those in mice, which is enough to give scientists insight into how our bodies work and how they change as we age. Lab mice have proven to be valuable allies in research on the complex biological process of aging.

“A detailed study of the natural aging process in humans is impossible,” says Johan Auwerx, the head of EPFL’s LISP. “In Switzerland, for example, you’d have to follow all the babies born in a given year for the following 70 years and then analyze all the data you collect. Apart from the related ethical and financial challenges of such a project, any one scientist can only conduct productive research for up to 35 or 40 years.”

To get around this problem, Auwerx and his colleagues launched the Healthspan Diversity Project in 2018. Their goal is to compare genetic data from mice, which have a lifespan of roughly two years, with data from humans to see if there are any parallels worth exploring. This has proven to be one of the most innovative aging-related studies conducted so far. “We hope to pinpoint the human genes associated with an accelerated decline in disability-free life expectancy,” says Auwerx.

An “atlas” of possible genetic factors

One of the reasons people age so differently is that there’s a large amount of diversity within the human population. The research group sought to factor that diversity into their project by studying 82 different strains of mice. That’s a fairly unusual approach in biomedical research, where scientists generally try to use mice that are as similar as possible to prevent other factors from influencing their research results. Some 4,500 mice – not counting those involved in the breeding process – are being used in the project. “First, we observed the mice very carefully for 20 months, which is equal to 70 years in human terms,” says Maroun Bou Sleiman, a scientist at LISP. “We did that using a 24-hour data collection system installed in their cages. We also ran full tests of the mice’s cardiac, metabolic and neurological functions twice during their lives. At the same time, we collected tissue samples from some mice, building up a database of 120,000 samples.” To obtain the samples, lab technicians at EPFL’s Center of PhenoGenomics euthanized mice of different ages and collected 27 samples from various types of tissue: liver, heart, muscle, kidney, eyes and more. Scientists then analyzed the samples and developed an “atlas” of possible genetic factors explaining why some mice live longer than others.

Now the Healthspan Diversity Project is entering the crucial phase of associating the mice data with those from humans. “We’ve sequenced the mice genome, and now we need to produce multiomic data – that is, data covering things like RNA, proteins and lipids – for each type of tissue,” says Bou Sleiman. “That’ll give us thousands of data points for constructing the full realm of aging possibilities in mice and examining aging trajectories in relation to clinical, physiological and molecular parameters. This is just the first step, albeit a huge one, and it should help us better understand what goes on in humans.”

We hope to pinpoint the human genes associated with an accelerated decline in disability-free life expectancy.”

The mice data will be compared to a vast set of genome data from hundreds of thousands of patients. These data are contained in clinical databases and are being used to study the role that genetic predisposition plays in the development of certain diseases. Auwerx explains: “We’ve already made some interesting discoveries. For instance, we found that reducing the accumulation of ceramides – a type of fatty acid – in muscle tissue can prevent muscle loss with aging, and that mitochondrial stress can contribute to the weakening of bone tissue.”

Predict the aging trajectory

The project team is now seeking funding to move forward with this large-scale analytical work, as the costs are high owing to the sheer number of tissue samples. And the funding is needed urgently: even though the samples are frozen, they age with each passing day, which can make it difficult to collect meaningful data. “We’re about halfway through the project, and it would be a waste of money and animals’ lives if we aren’t able to obtain more concrete benefits for humans,” says Auwerx.

One challenge stems from the fact that this project, while extremely important, is still in the realm of basic research and is too ambitious to be picked up by large pharmaceutical companies. Yet by identifying the genetic and molecular predispositions that we each carry – which is again an innovative approach – doctors can predict at least part of the trajectory our bodies will follow as we age and spot potential health problems before they arise.

We’re about halfway through the project, and it would be a waste of money and animals’ lives if we aren’t able to obtain more concrete benefits for humans.”

If we’re to believe the headlines, human immortality is right at our fingertips. Or almost. Magazine and newspaper articles regularly tout the latest methods – some scientific, some less so – for slowing the aging process, staying young, regenerating our cells and neurons, and living longer. For now, the only proven method is a healthy lifestyle: regular exercise, a healthy diet, a good night’s sleep and close social ties. But the search is still on for a magic pill. And although some promising new discoveries are in the works, the only creatures currently given a chance to live longer are lab mice, zebra fish, fruit flies and worms.

You are what you eat

It’s no secret that a key element of good health is good nutrition. But it can be hard to figure out exactly which foods to eat, in what form, and the best way to cook them. “Nutrition is one area where it’s difficult to provide concrete scientific evidence, because diet is just one of a multitude of behavioral, environmental and genetic factors that affect our health,” says Christian Nils Schwab, the head of EPFL’s Integrative Food and Nutrition Center. He also points out that this poor understanding of the scientific fundamentals of nutrition is why there’s a lot of debate over whether certain products – such as coffee, wine and milk – are good or bad for us. That’s especially true when it comes to aging, where it’s even harder to identify whether certain foods have positive or negative effects.

“For some foods, like vegetables and plant-based proteins, there’s obviously a consensus around the benefits,” says Schwab. “But that comes mainly from empirical evidence rather than scientific studies.” He goes on to explain why there’s still so much uncertainty: “Research currently tends to focus on treatment rather than prevention. Take metabolism – it’s generally thought of only in the context of treating metabolic disorders. But studying prevention can open up an array of amazing opportunities in life science. For instance, with a better understanding of how our metabolism works, we can help people stay in good health as they get older.”

One emerging field of research is precision nutrition, which considers aspects like genetics and personal habits when evaluating the overall effects of a healthy diet. Unlike the general guidelines given in the food pyramid, for example, precision nutrition entails developing food plans tailored to the needs of specific individuals. Schwab sees a lot of promise in this approach and believes science will produce the tools and systems needed to implement it – provided there’s a paradigm shift and we start thinking in terms of prevention and not just damage control. “For every Swiss franc spent on an unhealthy diet, two must be spent on repairing the harm done to the person’s health and to the environment,” he says.

For every Swiss franc spent on an unhealthy diet, two must be spent on repairing the harm done to the person’s health and to the environment.”

Recycling mitochondria

Without the energy needed to keep going, our cells will simply wither away. They get their energy from mitochondria – organelles known as the cells’ powerhouse. While healthy cells can recycle faulty mitochondria, research conducted by Prof. Johan Auwerx and his team at EPFL suggests this recycling process slows with age. The scientists also identified several factors that can promote mitochondria recycling, such as the presence of urolithin A, a postbiotic compound produced by gut bacteria as they break down the phenols in pomegranates, walnuts and raspberries, for example. The problem is that only 40% of us have a microbiome capable of synthesizing urolithin A effectively, and the conversion rate – or the amount of urolithin A produced from digested food – is still unknown.

Prof. Auwerx and his colleagues therefore developed a method for fabricating urolithin A so that it can be marketed as a food supplement. They founded Amazentis, an EPFL spin-off, that now sells the postbiotic under the Mitopure brand name. Clinical trials have shown that urolithin A can measurably improve patients’ muscle function. Mitopure is patent-protected in several countries and stands to help millions of people stay in better health as they age.

More recently, Prof. Auwerx’s research group discovered that the accumulation of ceramides (a type of fatty acid) in muscle cells interferes with mitochondria recycling, and that in mice, treatments to inhibit ceramide synthesis can promote this recycling – thus improving muscle health and slowing the aging process. These findings were published in Nature Aging and Science Translational Medicine in 2023.

Reprogrammed cells

Meanwhile, Japanese scientist Shinya Yamanaka was studying the process by which embryotic stem cells develop into differentiated cells in adults when he started looking at the process in the other direction: how differentiated cells in adults can be brought back to a pluripotent state – that is, back to how they were in the embryonic stage. The method he found – which won him the 2012 Nobel Prize in Medicine – is actually (relatively) simple. It involves adding four transcription factors, which are proteins that regulate gene expression, along with an activation factor to an adult cell in order to turn it into a pluripotent stem cell.

The idea here isn’t to reprogram all human cells (we’d lose our minds!), especially since the success rate is under 1%, but rather to turn back the clock a little. Studies on mice have shown that injecting these Yamanaka factors can rejuvenate cells and regenerate cell tissue. But since some mice also ended up getting cancer, the challenge is to find the right balance between the risks and benefits. For now, using this method to extend our lives is still the stuff of science fiction, and regenerating a mouse’s skin or kidney cells doesn’t necessarily mean it’ll live longer.

But that hasn’t stopped a number of Silicon Valley billionaires, first and foremost Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, from betting on this new approach. Bezos has invested millions in Altos Labs, a firm created in 2021 that brings together a number of leading figures in the field, including Yamanaka as scientific advisor. Altos Labs had amassed a record $3 billion in capital by January 2022. The company hasn’t disclosed many details but says its goal is to restore cell health and resilience through cellular rejuvenation programming.

how differentiated cells in adults can be brought back to a pluripotent state – that is, back to how they were in the embryonic stage.”

Off-label drug use

Sometimes, drugs prescribed to treat one disease have unexpected side effects that turn out to be beneficial for another. That was the case for metformin, introduced on the market over 60 years ago and now the most widely prescribed diabetes drug. Studies have shown that metformin can measurably reduce or prevent the development of three age-related illnesses: dementia, heart disease and cancer. It seems to attenuate the hallmarks of aging by delaying stem-cell aging, enhancing autophagy and intercellular communication, modulating mitochondrial function, and protecting against macromolecular damage. Metformin is believed to offer the same longevity benefits as a low-calorie diet. A US consortium wants to run a vast, six-year clinical trial with 3,000 participants, called Targeting Aging with Metformin, to test these benefits – but it still needs to raise the necessary funding.

Other scientists are investigating rapamycin, a cell-growth inhibitor and immunosuppressant commonly used to prevent the body from rejecting organ transplants. It also appears to provide benefits similar to those of a low-calorie diet. So far rapamycin has only been tested on fruit flies and mice, but soon dogs will have their turn through the Dog Aging Project.

Sometimes, drugs prescribed to treat one disease have unexpected side effects that turn out to be beneficial for another.”

Revitalizing DNA

As old cells wear out in our bodies, new ones replace them through cell division. During this process, the cells’ chromosomes are protected by telomeres located at each end. Without the protective telomeres, some DNA would be lost from a chromosome every time a cell divided. This would eventually lead to the loss of entire genes. But the telomeres themselves get shorter with each cell division, to the point where they get so short that the cell stops dividing. The cell then becomes senescent (see below) and contributes to aging. Telomeres are therefore an indicator of our biological age, as opposed to our chronological age (the number of years since birth).

Fortunately, there’s an enzyme called telomerase that can restore the bits of telomeres that are cut off during cell division, making cells virtually immortal. But the catch is that in humans, telomerase is found mainly in germ cells (sperm and egg cells), stem cells (in an undifferentiated state) and – unfortunately – cancer cells.

Therefore the use of telomerase is a double-edged sword: scientists must find a way to make somatic cells immortal without causing cancer. Research on mice has given promising results, provided that measures are taken to reduce the risk of cancer. But there’s no guarantee the same results will be found in humans. For now, most telomerase research is focused on finding a cure for cancer rather than finding the fountain of youth, although studies have shown that an unhealthy lifestyle, high alcohol consumption and high stress levels serve to shorten telomeres. Three scientists – Elizabeth Blackburn, Carol Greider and Jack Szostak – won the 2009 Nobel Prize in Medicine for their research on telomeres and telomerase.

Young blood

“Let there be a young man, robust, full of spiritous blood, and also an old man, thin, emaciated, his strength exhausted, hardly able to retain his own soul. Let the performer of the operation have two silver tubes fitting into each other. Let him open the artery of the young man, and put into it one of the tubes, fastening it in. Let him immediately after open the artery of the old man, and put the female tube into it, and then the two tubes being joined together, the hot and spiritous blood of the man will pour into the old one as it were from a fountain of life, and all of his weakness will be dispelled.” This was the age-defying method wittily suggested – but never tested – by Andreas Libavius, a German physician and alchemist, in 1615.

Fast-forward to the 2000s, when a team of US scientists tried a similar experiment, they joined the circulatory systems of two mice – one young, one old – and found that the old mouse got a new lease on life with improved muscle tissue and organ function, including in the heart and brain. Shortly afterwards, US companies began marketing young blood. For example, Ambrosia sold plasma bags for as much as $8,000 each. But the company stopped providing its transfusion procedure in 2019 after the US Food and Drug Administration warned against it, stating there was no scientific evidence it could treat illness or slow or prevent aging.

Scientists nevertheless continued their research to understand the mechanisms at work in this Dracula-esque approach. A team from

Columbia University tried turning the problem around. “A 70-year-old with a 40-year-old blood system could have a longer healthspan, if not a longer lifespan,” says Emmanuelle Passegué, Professor of Genetics and Development at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Her research group studied bone marrow, which is where blood stem cells are produced. They found that aging leads to a deterioration in bone marrow as it becomes overwhelmed with inflammation, causing dysfunction in blood stem cells. The scientists also discovered that an anti-inflammatory drug commonly used for rheumatoid arthritis – anakinra – can block this inflammation. They administered life-long doses of anakinra to mice and found it was effective in returning the mice’s blood stem cells to a younger, healthier state.

A 70-year-old with a 40-year-old blood system could have a longer healthspan, if not a longer lifespan.”

Getting rid of zombie cells

Another approach that Silicon Valley billionaires are investing in entails eliminating old cells from our bodies, based on the fact that we age because our cells age. Most old cells die, but some of them – known as senescent cells – stick around like zombies and accumulate. These cells secrete a number of proteins that impair tissue function, favoring the development of cardiovascular disease, cancer and dementia. But in 2015 a Mayo Clinic research group headed by James Kirkland discovered a new family of drugs, called senolytics, that can selectively eliminate senescent cells.

Today, around 20 biotech companies are spending billions of dollars to develop and market senolytics. But they’ve still got a way to go. One company – Unity Biotechnology – decided to halt phase 2 clinical trials on a senolytic in 2020 because it didn’t prove effective against osteoporosis. What’s more, a study appearing in Science last October concluded that not all senescent cells are harmful: some of them are embedded in young, healthy tissue and promote the normal repair of damaged tissue.

First of all, it’s what most of us want – to grow old peacefully in our own homes. In Switzerland, only 15 out of every 1,000 people aged over 65 live in a nursing home. And second, it’s a cost issue: each year in a nursing home costs approximately five times more than a year living at home. There are also the broader economic benefits of the “silver economy” – the promising market of senior citizens who generally have high purchasing power. The aging population is opening up opportunities for businesses that provide goods and services targeted to this age group. As we get older, it’s almost inevitable that we’ll start having health issues and our consumption needs will change. “Living on your own doesn’t mean sitting at home all day – you have to be able to do the shopping, run errands and handle household chores, for instance,” says Delphine Roulet Schwab, a professor at the La Source School of Nursing and the co-head of senior-lab, a university consortium that conducts cross-disciplinary research to improve senior’s lives.

A growing number of solutions, many of which draw on the latest technology, are being rolled out to assist people as their health starts to decline. These include vital-sign monitoring systems, gait sensors, stairlifts and domestic robots – products designed to help people get around, cope with the symptoms of Alzheimer’s and reduce the risks associated with falling. A gerontechnology initiative called Autonomie 2020, launched jointly by institutes in France and Switzerland, has identified dozens of technological developments in this area. EPFL engineers are also hard at work; they’ve developed a hand exoskeleton to help stroke victims grasp objects, marketed by EPFL spin-off Emovo Care; a smart ring that monitors health parameters, marketed by EPFL spin-off Senbiosys; a device that detects falls, marketed by EPFL spin-off Gait Up; and a digital application to coordinate patient care, marketed by EPFL spin-off domo.health. Other systems are in the works based on advancements in robotics, connected health, the internet of things and remote sensors. Demand for these kinds of products and services is set to be huge: according to a report on the silver economy (in French) issued by the canton of Vaud, senior citizens are rapidly adopting new technology, and direct spending on high-tech devices by the over-65 age group could reach seven billion francs in Vaud by 2040.

First of all, it’s what most of us want – to grow old peacefully in our own homes.”

Technology is useful, but within limits

“Technology will be part of the solution,” says Roulet Schwab. “It’ll let some people live on their own for longer, easing the burden on their loved ones, who will then be better able to provide care over the long term. The problems arise when technology is used excessively, as a knee-jerk response to everything. We’ve got to make sure we take advantage of the benefits but without potentially violating individuals’ basic rights.” She cites the example of systems used to locate residents within a nursing home. Are they used only for a few hours a day to monitor someone who has a tendency to get lost, or are they used on everyone all day long? “Technology isn’t a panacea,” she explains. “We should be able to adapt as people’s needs change.”

And because their needs change, we need to start thinking of new, more flexible approaches to caring for the elderly. “Right now, family members have basically two options for someone who can no longer live independently: either set up in-home care, or place the individual in a nursing home,” says Roulet Schwab. “What’s missing are more adaptable, personalized alternatives where people pay for only the services they need. But that will require thinking out of the box and looking beyond the financial aspects. Innovative approaches are needed that are not just based on technology but on a new financial and social model.”

Technology isn’t a panacea. We should be able to adapt as people’s needs change.”

Connected health within the home

Some of the new technology – such as remote monitoring systems that incorporate domestic robots and connected medical devices – fits in with this kind of holistic approach. “One of our products is designed to let people who are starting to have health issues continue to live at home,” says Guillaume DuPasquier, an EPFL graduate and co-founder of domo.health. “It can detect and even prevent serious problems – like someone falling with nobody around to call emergency services, since in these cases time is of the essence – and send doctors real-time information on a patient’s respiratory rate and other vital signs, so the patient can get better care.” Connected medical devices can give doctors key information on a patient’s sleeping patterns, mobility and lifestyle habits, sending instant alerts when needed. They can also generate monthly reports to review during doctor’s visits, allowing for more personalized treatment protocols. “Here artificial intelligence will play a role, as AI algorithms can scan through vast amounts of data, spot anomalies and produce summaries – things doctors don’t have time to do,” says DuPasquier.

Social ties are just as important

But technology can’t do everything. “We need to get away from silo thinking and consider all the factors involved, from urban planning and transportation systems to finances, support networks, the job market and more,” says Roulet Schwab. “Take people who live in residential areas where there’s little or no public transportation. How will they manage when they can no longer drive?” That’s one reason why maintaining social relationships is so important for staying in good health. Studies have shown that satisfying social relationships can reduce the risk of developing chronic conditions as someone gets older.

Andrew Sonta, a tenure track assistant professor at EPFL, believes that his field of civil engineering can also be applied to reduce isolation among the elderly. For instance, cities and neighborhoods can be designed for residents to get around on foot rather than by car. “That will encourage more active lifestyles and make it easier for people to make friends and acquaintances,” he says. And because social connections are so important, neighborhoods can combine housing with shops and offices in order to bring people together and avoid districts that residents commute to only for work. “This would make people more likely to help each other out in the event of difficulty or an extreme weather event, like a heat wave, resulting from climate change,” says Sonta.

That will encourage more active lifestyles and make it easier for people to make friends and acquaintances.”

Understanding technology adoption factors

Scientists at the EPFL+ECAL Lab are also addressing the topic of old-age dependency. They conducted a study to better understand the factors that encourage the over-65 to adopt new technology, and used the findings to design a digital application called Resoli that helps senior citizens connect with each other. “We know how crucial social relationships are for staying in good health – both physically and mentally – as we get older,” says Nicolas Henchoz, director of the EPFL+ECAL Lab. “And digital technology can help, but systems have to be designed to facilitate adoption, which means understanding the adoption factors for this age group.” The EPFL+ECAL Lab has spent several years working with senior citizens through Pro Senectute Vaud, a local nonprofit organization. “We saw that when users said a program was ‘too complicated,’ it rarely had to do with their technology skills,” says Henchoz. “It was just that they didn’t see the benefits of learning to use the program.” So instead of over-simplifying their program – and creating an application that could potentially be stigmatizing – the developers focused on the adoption factors identified in the study: trust, credibility and concrete benefits. “We found this led to applications that are more appealing to younger users, too,” says Henchoz. “Because in the end, the barriers to adoption among seniors are actually common to us all.”

We know how crucial social relationships are for staying in good health – both physically and mentally – as we get older.”

The issue isn’t so much that women have longer lives in absolute terms or that they age more slowly, but rather that men die younger. That’s partly because they tend to engage in riskier behavior. Is this due to testosterone, or to the fact that their frontal lobe develops more slowly than in women? Men are more likely to die young behind the wheel of a car, on a bicycle, up in the mountains, in a duel or from suicide. They’re also more likely to smoke, drink, be overweight, have dangerous jobs, avoid going to the doctor and fail to follow the doctor’s instructions when they do.

The higher level of testosterone also lowers men’s immune-system response, and increases the risk of heart disease. Estrogen, on the other hand, plays a protective role. What’s more, Y chromosomes are more prone to developing mutations than X chromosomes, and men don’t have a spare X chromosome – like women do.

This life expectancy gap isn’t limited to homo sapiens – it exists in most mammals. An international research group headed by Jean-François Lemaître, a CNRS researcher at the University of Lyon’s Biometrics and Evolutionary Biology Laboratory, compiled demographic data from 134 mammal populations encompassing 101 species such as bats, lions, killer whales, gorillas and more. For 60 % of the populations, females live longer than males – an average of 18.6 % longer (the gap is just 7.8 % for humans). It’s interesting to note that the scientists didn’t find a difference in the rate of aging between the sexes. Instead, their findings suggest that the gap is predominantly shaped by complex interactions between local environmental conditions and sex-specific reproductive costs.

Life expectancies have been climbing around the world over the past 100 years except in times of war and in a few countries such as the US, where life expectancy is falling due to the opioid epidemic. “But we’re also seeing greater disparity in just how much life expectancies are increasing, including within a given urban area,” says Mathias Lerch, the head of EPFL’s Urban Demography Laboratory. In other words, how long you live could depend on whether your home is in a city, in the suburbs or out in the country. In Switzerland, life expectancy can vary from one canton to the next: a resident of the canton of Geneva, for example, is likely to live two and a half years longer than someone in the canton of Glarus.

Take a closer look, however, and the reality is much more nuanced. Scientists in Lerch’s lab are studying such “life-expectancy maps” in order to identify the main factors at work, whether in terms of urban development structures, lifestyles or the living environment. “Before the industrial revolution, life expectancies and general health were worse in cities than in rural areas owing to epidemics, overpopulation and poor healthcare systems,” Lerch explains. “That changed after the industrial revolution and the introduction of basic hygiene practices. But since the 1960s, and especially in Switzerland, life expectancies in cities have become lower than in the suburbs and are now on par with figures in rural areas.”

The role of environmental factors

To understand why that is, Lerch examined all the possible variables that could influence life expectancies. And there are a lot. Take a city’s sociodemographic profile, for instance. “Swiss cities experienced an exodus in the 1960s when people moved out of the center and into the less-congested suburbs,” says Lerch. “These were mainly people in the upper-middle class, who are better equipped both financially and education-wise to adopt healthy lifestyles. These also consisted mainly of families, and family environments are a known factor in increasing life expectancy by several years. Concomitant with this exodus, a number of negative social and psychological factors emerged in city centers. Urban life is more stressful, with people living anonymously among neighbors from different backgrounds and cultures. That makes it hard to form social bonds. We also found that certain lifestyle habits in city centers can lead to a higher incidence of cancer, for example, which shortens life expectancy.”

Environmental factors play a role too. For instance, we now know that heat waves kill. And during heat waves, temperatures are often a few degrees higher in cities – due to their high construction density and lack of green spaces – than in the country. We also know that noise pollution, especially at night, can cause elevated stress levels and even cardiovascular disease, as demonstrated in a 2018 study conducted jointly by EPFL, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) and the Geneva University Hospitals (HUG). The greater air pollution in cities makes residents less likely to exercise outdoors, and poorly constructed buildings, particularly if they’re dilapidated or have insufficient noise and heat insulation, can also have an impact on health. On the other hand, it’s often easier to access public services, including healthcare facilities, if you live in a city.

Individual behavior is another factor contributing to longevity. Lerch attributes the relatively lower life expectancies in rural areas to higher accident rates and to a greater occurrence of cancer, mainly from alcohol consumption. “We saw this pretty clearly in the cantons of Jura and Valais, although the difference has been narrowing in recent years,” he says. “There’s also more cardiovascular disease and heart attacks in rural areas, which could be due in part to the greater difficulty in accessing healthcare and to a less prevention-oriented mindset.” As mentioned earlier, social bonds and family environments can go a long way towards increasing life expectancy, as they often encourage healthier behaviors. That’s true for education, too. The life expectancy of a 35-year-old with a postsecondary education is seven years longer than that of a 35-year-old without such an education. “Generally speaking, discrepancies in life expectancy tend to be more pronounced among men than among women,” says Lerch. “That also suggests individual behavior is a key driver, as men tend to engage in riskier activities.”

Generally speaking, discrepancies in life expectancy tend to be more pronounced among men than among women.”

A selected migration

While the broad trends are easy to identify, Lerch warns that we should be careful not to generalize: “It’s hard to know exactly where people had the longest exposure to their environment. The place where someone lives their final years isn’t necessarily the one where they spent most of their life. That’s especially true in today’s urban society where a lot of people migrate. Another issue to consider is whether we should look at where someone lives or where they work. Sometimes the workplace can be much riskier.”

Migration is a big reason why life-expectancy maps are continuously changing. “City centers attracted many residents in the 2000s, but these days middle- and upper-class families are once again moving out to the suburbs,” says Lerch. “We’re also seeing that during heat waves, those who have the means – primarily the older age groups – relocate to higher altitudes. This trend is set to increase.”

Life-expectancy statistics can also be biased by external factors – such as immigration. Immigrants in Switzerland have a proven effect on life expectancies in various regions. They tend to increase life expectancies in cities, including in the Lake Geneva area where, according to a 2018 study, the presence of a selected migrant population raised the average life expectancy by 1.2 years for men and 0.6 years for women. “This is known as the ‘healthy migrant’ effect, since these people decide to emigrate while in their home country and are generally young and in good health,” Lerch explains. “There’s also the ‘salmon effect’ whereby immigrants return to their home country after they retire and spend their final years there, meaning their deaths aren’t reflected in Swiss statistics.”

The place where someone lives their final years isn’t necessarily the one where they spent most of their life.”

Proposed pension reforms have triggered wide-spread protests in France, divided Switzerland in recent referendums and are a source of ongoing debate as the population ages. Are citizens right to be so worried about their retirement? “It’s the most important issue for people when it comes to their personal finances,” says Dorothea Schmidt-Klau, senior economist at the International Labour Organization’s Employment Policy Department. “In most countries, an individual’s pension is their only source of income, apart from those in the wealthiest social classes.” An insufficient pension can also tip people into poverty – a risk that concerns us all. A child born in Europe now has a 50% chance of living to be 100. In Switzerland, 19% of the population was over 64 in 2021, and according to the United Nations, 1.6 billion people will be in the over-65 category by 2050.

Proposed pension reforms have triggered wide-spread protests in France, divided Switzerland in recent referendums and are a source of ongoing debate as the population ages. Are citizens right to be so worried about their retirement? “It’s the most important issue for people when it comes to their personal finances,” says Dorothea Schmidt-Klau, senior economist at the International Labour Organization’s Employment Policy Department. “In most countries, an individual’s pension is their only source of income, apart from those in the wealthiest social classes.” An insufficient pension can also tip people into poverty – a risk that concerns us all. A child born in Europe now has a 50% chance of living to be 100. In Switzerland, 19% of the population was over 64 in 2021, and according to the United Nations, 1.6 billion people will be in the over-65 category by 2050.

Inequality when it comes to arduous jobs and disability-free life expectancy

What can governments do in response? Oris believes that increasing the retirement age is one option, but there are others. He says governments should especially consider those working in arduous jobs, along with other workforce inequalities. “Life expectancy in Switzerland has increased considerably since our social security system was introduced – but the retirement age is still the same,” he says. “That’s something we could think about.” He feels it would be fair to increase the retirement age for some groups and lower it for others, since not everyone has the same postretirement life expectancy, nor will they all live those years in good health. The over-65 age group contains a broad mix of people in terms of education level, health condition and gender. And while it’s true that life expectancy has risen in general, disability-free life expectancy – or the number of healthy life years an individual has remaining – can vary widely. Studies have shown that since the turn of the century, disability-free life expectancy has risen continually for people with a high-school or college education but have stagnated for those with a lower level of education, particularly among men. “Gender differences also need to be taken into account,” says Oris. “Women live longer, but with more health problems.”

In most countries, an individual’s pension is their only source of income, apart from those in the wealthiest social classes.”

Other options

In terms of other factors to consider, Oris points to the productivity gains in rich countries, which have increased governments’ tax revenue (since more productive workers lead to higher earnings). In Switzerland, a lot of women work part-time, meaning there’s potential to bring them in further and expand the workforce. And there’s the issue of immigration. “The types of people who emigrate to Switzerland have changed quite a bit,” says Oris. “Today we’re seeing a lot of college graduates with skills that are missing in the domestic job market. These people will be among those who pay a lot into the social security system.” According to Schmidt-Klau, governments must find a way to increase the size of the workforce in order to fund their pension systems. This could include encouraging those who are over 65 and who want and are able to keep working to do so, such as by adapting their working conditions and workplace. “Similar incentives could also be given to women, young people and any other category where there’s scope to increase the labor force participation rate,” says Schmidt-Klau.

But for all that to work, we also need to change society’s perceptions of senior citizens. Agism – discrimination based on a person’s age – is still very much an issue, especially in the job market. Older workers are often associated with reduced productivity and higher costs. “But these employees bring valuable experience, and studies have shown that thanks to lifelong learning, they have no more trouble than their younger counterparts in acquiring new skills,” says Schmidt-Klau. “But that requires long-term investments in training and education.” She also notes that bringing senior citizens into the workforce doesn’t mean there will be fewer jobs available for young graduates. The two groups don’t have the same qualifications and competencies. “In fact, research has suggested the opposite,” she explains. “When employment rates increase among seniors and women, they also increase among youth and men. And if we can ease the problem of poverty among the retired, that also benefits younger people.”

Overblown baby-boomer fears

Some analysts warned of collapsing pension systems as baby boomers – the generation born between 1945 and 1964 – reached retirement. But those doomsday scenarios haven’t materialized. Oris explains: “Analysts were worried about the sheer number of people retiring at the same time, but these kinds of warnings have been around for years. When baby boomers all started going to school, the educational system didn’t collapse. And when they hit the job market, unemployment rates didn’t skyrocket. People have been making catastrophic predictions for decades, but you can’t make forecasts by looking at the issue from just one angle.”

Other doomsday scenarios associated with the aging population relate to rising healthcare costs and whether countries will be able to maintain their existing healthcare systems. The FSO estimates that Swiss healthcare costs amounted to 11.8% of GDP in 2020, compared to 8.8% in 1995 and just 4.9% in 1960. So it’s true that healthcare costs are escalating, but Promotion Santé Suisse notes that public-health economists have warned against simplistic interpretations of the correlation between healthcare costs and age. They point out that the cost driver isn’t advancing age but rather proximity to death. The report cites a Swiss study that found that an individual’s need for healthcare – and therefore the associated (hefty) healthcare expenditures – increase in the last year of life, regardless of age. What’s more, several organizations have concluded that technological innovation is a major contributor to rising healthcare costs. The FSO views the rising costs as “a complicated trend being driven by several factors including the number of patients needing care, the amount of care needed for each patient, the cost of that care, stressful lifestyles, fewer social ties between generations and more.”

The importance of healthy life years

Statistically speaking, an older population automatically translates into greater healthcare needs – especially for those who are in poor health or who have become dependent. Increasing the number of healthy life years, which would entail adopting policies to promote healthy lifestyles, can therefore reduce healthcare costs significantly. Promotion Santé Suisse estimates that over 11 billion francs could be saved by reducing elderly dependency.

This is consistent with Oris’s findings. He confirmed that the groups generally referred to as senior citizens (the newly retired, who have more freedom and leisure time) and the elderly (those over 80 who experience some of the things people fear most about aging – such as becoming senile and losing their independence) are made up of people from many different backgrounds and in many different situations. “In the over-80 age group, some people remain in fairly good shape, the majority of them become frail but can still do most things on their own, and a large minority – around 45% – become dependent,” says Oris. “We need to work on delaying this dependency for as long as possible.”

Some economists have raised the issue of how the aging population will affect governments’ tax revenue. Most fiscal income in Europe comes from social security contributions, income taxes, and sales and property taxes. But the changing age pyramid could alter that. Fewer working-age people could mean less taxes being paid along with shifts in consumer spending patterns. Oris sees this as strictly a political issue. “Left-leaning parties have been saying for years that there are options for making up the shortfall,” he says. “For instance, financial transactions haven’t been taxed since the 1980s, and much of today’s economy sits outside the tax system. Changing this could be part of the solution.”

We need to dispel the myth that old people are a costly burden on society. We’re all getting older together – we’re in the same boat.”

New consumer habits and opportunities

Economists are also looking at consumer spending habits, since people in different stages of life have different needs, wants and financial resources. Some industries – like personal care, travel and pharmaceuticals – stand to gain from the aging population, and they will be the ones that create jobs and wealth. “Aging has always been seen as something negative, but in the developed world, retired people are relatively well off,” says Schmidt-Klau. “They have money to spend. If we adapt our economies and make the most of the potential this represents, that could completely change society’s perspective.”

The list of challenges we’ve given here is far from exhaustive. Yet one possible solution for addressing them is to build closer ties and understanding between generations. “We need to dispel the myth that old people are a costly burden on society,” says Oris. “We’re all getting older together – we’re in the same boat.”

Can modern healthcare extend life at any cost?

The primary goal of healthcare isn’t to make us live longer. Rather, it’s to treat disease and provide care. And if the result is a longer life, that’s great! But these lives have to be “worth living” in that they have meaning, are nourished by relationships, etc. And even here, we need to be clear: it’s humans as individuals – and not their lives per se – that have dignity and should form the basis of all ethical decisions. Those who are irrationally obstinate in extending life are driven by a determination to maintain “life” at any cost. But today, nearly everyone views that approach as unreasonable.

Why are we so eager to become immortal?

When we’re with people we love and have a meaningful life, we want to live forever! It’s hard to come to grips with the fact that our loved ones will die. Some people, like Christians, believe in eternal life – that is, life with and within Christ, in a resurrecting Love. Others, like transhumanists, believe we can “upload” our brains and become amortal (except in the event of an accident or suicide). And still others hold to the fact that memories survive after someone passes away – that’s the belief Shin Ha Kyun explores in Yonder (a TV series released in October 2022). The final words of the protagonist, Jae Hyun, are telling: “Memories are precious because they reflect moments that we experience only once.”

Is assisted suicide a consequence of today’s longer life expectancy, in a society where people increasingly reject ill health?

It’s more complicated than that. In a technology-driven society like ours, we’re encouraged to believe that we can control all aspects of our lives and that such total autonomy on an individual level is possible and realistic. One result of that is people want to decide for themselves how they live and how they die, including through assisted suicide. But actually, as I explain in my writing on vulnerability, humans are relational. We’re porous beings, when it comes to both positive things (love, friendship, conversation, etc.) and less positive things (evil, illness, hatred, etc.). We need to develop a society in which we each get what we need and enjoy personal dignity.